Cheryl Strayed is best known for Wild, her memoir of hiking solo on the Pacific Crest Trail, but she’s also been a novelist, essayist, and advice columnist for the New York Times and The Rumpus. We caught up with her ahead of her keynote speech at this month’s Tea & Tonic fundraiser at the Center for Community Solutions, a San Diego domestic violence shelter, to talk about activism, fan feedback, and writing fiction versus reality.

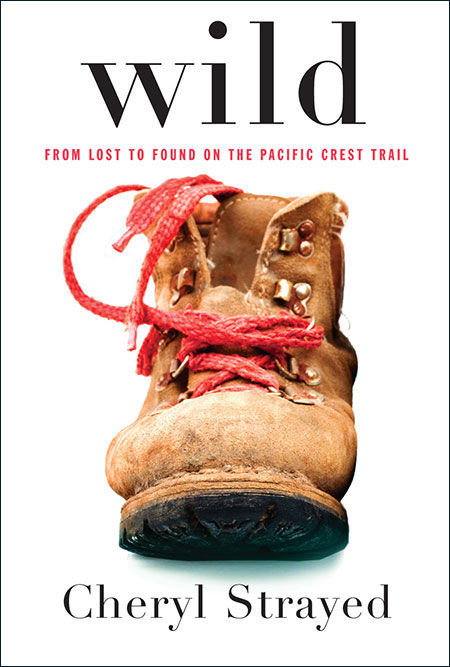

‘Wild’ Author Cheryl Strayed Comes to San Diego

You worked as a women’s rights activist and political organizer even before your writing career took off, correct?

All my life. As a child, I experienced domestic violence in my home, so this is a cause and a mission that’s very close to my heart. I’m always trying to help others in the communities I’ve lived in, and that started very early with women’s rights.

You’ve published a novel, a memoir, and advice columns. Is there one kind of writing that most motivates you, or does it change?

I think story is story. We combine imagination and experience one way in fiction, and in a different way in memoir and creative nonfiction. The advice columns are very much personal essays; I help by way of telling stories from my own life. That was something I just sort of fell into. I was asked to write Dear Sugar, and next thing you know all of these people were actually reading—which was a surprise to me! But I think I’ll be moving back and forth between fiction and nonfiction all my life. You have to do the same thing in both: tell a compelling story and make that character feel real to the reader, whether that person actually exists in real life or not.

Now that you have a few books out, is writing longform less challenging than it used to be?

I wish I could say that now it’s really easy to write books. Every book is hard, and I am in a slightly different position now. Throughout my first two books, the world wasn’t waiting to read what I wrote. But now there are all these people saying, “When’s your next book coming out?” When I was writing Dear Sugar, it would go up on the website and five minutes later there would be comments. That immediate rush of praise or condemnation. For books, you toil away for months or sometimes years on end and have no idea what anyone is going to think of it. But I think the only way to write is to shut out the voices of others. You have to, in order to do the work that you’re really meant to do.

My favorite Dear Sugar column is The Ghost Ship That Didn’t Carry Us; in it you advise someone in his late 40s who’s unsure about having children, wondering whether he’ll regret not doing so later on. What do you do with that question, of whether what you’re doing now is what you’re supposed to be doing, whether it’s honoring what you previously imagined your life might be?

In my 20s and 30s, when I had to have jobs that weren’t really my passion, sometimes I would get so upset because I would think, “I’m here to be a writer; that’s what I have to give to the world.” And yet, of course, I had to pay the rent. That constant struggle between practical concerns and the bigger picture. But that question, “I kind of want kids, but I also kind of like being able to do whatever I like now”—what I said to him was, that’s totally valid. Maybe the meaning of your life is that you don’t burden yourself with children and instead use all that time to do something else that’s really important to you. There’s no one answer. The only answer is, don’t be the person who never makes the decision and therefore never does anything meaningful. I think that’s where a lot of people get caught up. Even during all those years I was waiting tables, I never lost sight of my vision for myself and I did things to work toward it. Living with intention is always the important thing: to really think about the choices you make. They matter a little bit in the short term but they matter a lot in the long term.

It brings to mind that beautiful passage from The Bell Jar, where she imagines all the different futures her life could take like figs in a tree, one with a husband and kids, one as a famous poet, and so on, all of them shriveling up because she can’t choose. It’s such a wasted, paralyzed feeling; you have to live the life that you’ve chosen.

Yeah, I think you do. There’s this big bias in our culture that the meaningful life is the one in which you have children. And even though I would tell you that having children is the most meaningful experience of my life, I also know that if I hadn’t, there would be something else. You don’t want to spend your life in regret. But it’s also okay to see that other life you didn’t have and honor it. To think, “That would have been interesting too; there are real reasons I didn’t become those other things, but that doesn’t mean that they wouldn’t be valuable.” I was trying to use that as an assurance to him—whatever you choose, having a kid or not, you’re not going to make the wrong choice.

You’re the guest editor for this year’s Best American Travel Writing. People who are new to the genre might imagine that it’s not too dissimilar from what you’d find in, say, Lonely Planet—but Wild is as much if not more about your own interior journey than about how lovely the Pacific Crest Trail is.

I think Wild is both a travel book and not a travel book. Of course, it’s about a trip, and who doesn’t love reading about trips? It’s one of my favorite genres because you get to have that sense of going on a journey with somebody. But like every genre, people can tend to put travel writing over in a separate category, which I find a little unfortunate. I understand why the series has set the category aside—people who want to read about others’ journeys are going to find that here—but some of the best travel stories are also some of the best general literary essays. As an editor, I’m looking for work that is about travel but also meets that higher standard that we would apply to work outside the genre.

Good writing is good writing.

Yeah. Look at Ursula LeGuin, what a champion she always was for that. “I’m not going to be put into a box; I’m going to write all kinds of things, and they are all literature.

My favorite moment in Wild is when you come across the little boy who’s having some kind of trouble with his mother at home. The one who sings “Red River Valley.” You don’t get any real details of what’s going on, but that short interaction is written and shot so vividly, you feel what that trouble must mean to him, and it’s so much more powerful than if he had, like, monologued his life story.

Thank you so much. That’s a scene that’s close to my heart. When I’m writing nonfiction I’m scanning my mind for memories that create the opportunity to show the things I want to show. Everything in that scene really happened, and writing about it turned it into something that other people can feel, too. I think that’s what good writing does. It’s very similar to writing fiction, just a slightly different toolbox.

No matter what form you’re working in, you always connect with people and help them feel less alone—I’m sure it must do the same for you in turn.

Absolutely. Literature has been my consolation.

Meet the Author

Center for Community Solutions Tea & Tonic fundraiser

April 6, Hyatt Regency La Jolla at Aventine

‘Wild’ Author Cheryl Strayed Comes to San Diego