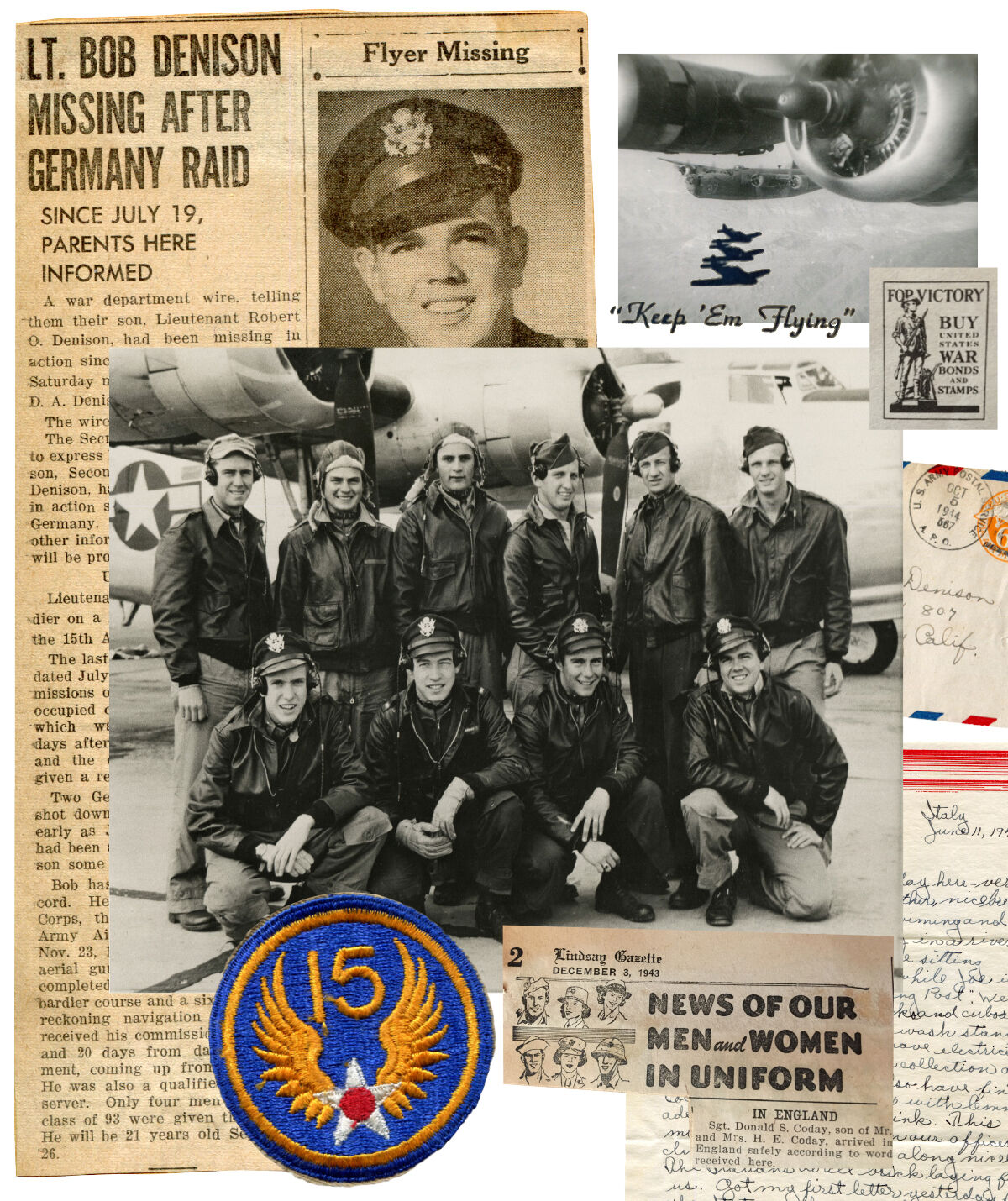

The Crew of the Little One—Rear: Charles Cartmille, ball turret gunner; Merle Weik, top turret gunner; John Lewis, tail turret gunner; Guy Howard, radio operator; Robert Marcum, nose turret gunner; Bob Garin, flight engineer. Front: Lt. Joseph Lidiak, navigator; Lt. John Rucigay, copilot, 1 Lt. Tom MacDonald, pilot; 2 Lt. Robert Denison, bombardier.

Robert Denison was serving as the bombardier aboard a B-24 when he was forced to bail out, separated from his crew, and survived for 40 days in Nazi-occupied Yugoslavia. In commemoration of Veterans Day, our copy chief put together this story, of his grandfather’s last mission in World War II. What follows is a composite, assembled from spoken and written accounts he gave over the years.

Between May and July of 1944, I flew 17 missions over Europe in the B-24 Liberator Little One. Most of the 10 men in our crew were fresh out of high school. I was just 19 years old, and the pilot was the “old man”—at 23.

Our plane was built right here in San Diego. As part of the 15th Air Force, we were sent to Pantanella Airfield in Southern Italy, to replace a crew who had just been lost. Over the previous year, the 15th alone had lost 186 planes.

We flew missions to Northern Italy, Bulgaria, Romania, Slovakia, and occupied France without major incident. Then on July 19, we embarked on our final mission—the one where we flew out and walked back.

When the curtains went up in the briefing room, they revealed our target: the BMW Aircraft Engine Factory in Allach, Munich—the third-most-defended city in the Reich, and we all knew what that meant. It was our first mission over Germany, and the chaplain announced that any Jewish soldiers among us could ask to be excused from it without fault.

Last Flight of the Little One

The entire 15th Air Force took part in the raid—nearly 3,000 planes in formation at once. We took off like an assembly line, in 20-second intervals.

It was very cold in the plane. I had to wear two sets of work clothes, my flight suit, my winter flying jacket, and even a second pair of fleece-lined boots over my GI boots. You could rest your beers on the bomb bay doors and they’d stay ice cold.

Things started going wrong before we were halfway to the target. First our new navigation unit caught fire; then Engine 1 quit on us. With just three engines, we had to drop out of formation and fell to a lower altitude.

“I painted our plane’s nose art myself, out on the tarmac in the rain. ‘Little One’ was the pilot’s nickname for his wife.”

The sky over Munich filled with bursts of antiaircraft fire; it got so close I could hear the shrapnel tinkling on the hull. Since we’d broken formation, we had to pick out a different “target of opportunity” to hit; then we banked to head for home. Only then did someone notice the holes shot through the wings. It was shortly after noon.

When Engine 2 went out as well, all the aircraft’s power was coming from one side, creating a constant midair skid. The flak also shorted out our electrical system, which meant no power for the turrets, the radio, most of the instrumentation—or even the flight controls. Now the only force keeping the plane level was the pilots’ own physical strength, same as losing power steering in a car. They stood up and put all their weight on the rudder pedals to keep us from entering an uncontrollable tailspin. I relieved the engineer on the waist guns so he could go up and help the pilots. Unfortunately, this meant I could no longer keep track of our position.

We flew south for another hour until we passed over a well-defended city and the sky filled with flak again. Then, who should appear but two red-tailed P-51 Mustangs—those brave Black pilots of the Tuskeegee Airmen.

They could see we were in trouble. One flew closer to the city to draw the enemy fire, and the other came up alongside and escorted us awhile. We communicated with him out the window by sign language, since our radio was out. He smiled, and wiggled his wings. Eventually he had to return to his own mission.

Soon after that, Engine 3 failed. After three hours of fighting to stay airborne, we were down to 11,000 feet and falling. There was no way to make it home with a single engine.

The pilot gave the order to bail out.

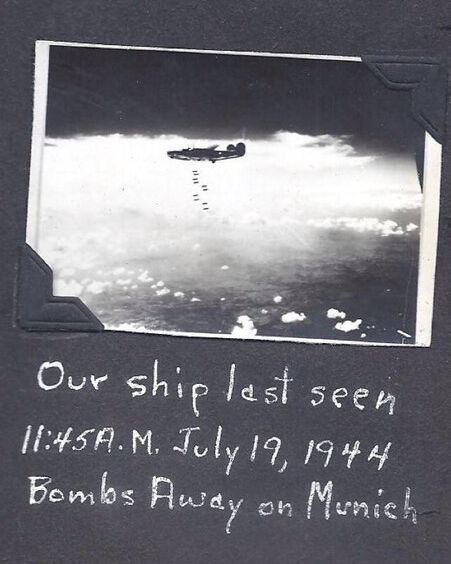

The Little One releases its payload while flying with other B-24s of the 464th Bomb Group, 15th Air Force.

Abandon Ship

I relayed the order to the four airmen in the waist gun section. They all just stared at me and shook their heads. “No sir,” they said. “After you.”

No time to argue. I opened the rear hatch and told the men to head southeast once they hit the ground, so they’d reach the Allied front line. We were turning back over land from the ocean, and I assumed we’d made it to the main “boot” of Italy, south of Venice. I was wrong.

I was first to tumble out. I caught a glimpse of everyone else opening their parachutes right away, high above me, but I knew what easy targets that would make us to ground fire, so I waited to pull my ripcord until I was just 300 feet up. We were trained to roll as we landed, to distribute the impact evenly—but in the confusion of the moment I tucked my knees and smacked hard heels-first, spraining my ankles.

This photo shows Denison’s actual plane.

I was in a cornfield, and a three-gun antiaircraft battery was close enough that I could hear the soldiers’ voices. They also had two German shepherds—who were both looking right at me and barking.

I lay on my back, my ankles throbbing in pain, trying to gather my thoughts and expecting to be taken prisoner at any moment. I rolled up my parachute and took off my jacket, which was covered with identifying insignia. Now I saw that the dogs were wagging their tails. To my astonishment, no one came.

So finally I crawled away into a dry irrigation ditch at the edge of the field, where I hid my jacket and parachute. A little more safely out of sight, I decided to rest and give my ankles some time to recover. I kept looking around for my crew but never saw them. Having opened their chutes much earlier, they could have drifted miles away before landing.

Before I knew it I’d fallen asleep. I was awakened in the middle of the night when the gun battery opened fire—the sound shook me to pieces. British bombers were flying overhead, heading southwest.

Veterans Day / Little One’s Flight Path Map

Finding Food, Water, and a Boat

The next morning I ate some raw corn and took inventory of my escape kit: bouillon cubes, matches, needle and thread, a compass, waterproof silk maps of Europe, and 42 US dollars. Too late I realized I’d left my .45 pistol behind in the bombardier’s position when I went to relieve the engineer. My only personal item was the wristwatch my parents had given me at my high school graduation two year ago.

As soon as I could bear putting weight on my ankles, I set out, slowly and limping. The countryside looked just like California. I knew the Allies were gaining ground every day, so we were bound to run into them if we just kept heading southeast.

I picked up more corn and some tomatoes to eat as I passed through the fields. To my surprise, by late afternoon I reached the ocean. I’d had no water all day and was feeling awful, so I drank some seawater. Of course, following the coastline south, the next thing I came upon was a rock quarry where fresh water had collected in the bottom levels. I drank up all I could.

It was dark by the time I came to a small cove with an unattended boat. I swam out, untied it, and quietly rowed to sea. I was already exhausted, but I knew night would be the safest time to travel, so I followed the shore for hours and hours.

Based on how long we’d been flying since Munich, I expected to be just northwest of San Marino—but the coast was turning southwest, which didn’t resemble anything in that part of the map. So where was I?

The moon was just a tiny sliver. In the darkness, the water at the stern glowed softly green—phosphorescent algae, churned up by the oars. By the time dawn approached, I couldn’t row any longer. I returned to shore, found the nearest shelter from the wind, and fell right to sleep.

Saved by a Song

I walked along the coast for days, eating what I could from the fields I passed through. Eventually it became clear that I wasn’t going to just stumble upon friendly troops—I’d have to risk turning west, toward the village centers, and asking someone for help.

On the sixth day after bailing out, I spotted a well behind a farmhouse. I was so excited by the thought of fresh water I went straight for it—and didn’t notice the farmer and his dog coming out to meet me there.

We got to the well at the same time. His wife and daughter were standing in the doorway, watching us. I gestured asking for water, and the farmer asked, “Parla italiano?”

I shook my head no.

Then he said, “Sprechen Sie Deutsch?”

I knew I had to fake it somehow. The puppy was tugging on my pant leg, so I knelt down, started playing with him, and sang the only thing I could remember from the German class I’d taken in junior college: “Die Lorelei,” a poem that, incidentally, is about a siren leading a pilot to shipwreck.

When I looked up, the farmer was smiling. He probably thought I was some harmless nut. The family brought out some bread, and when they drew up the bucket from the well, it was full of beer!

A half mile down the road I stopped and turned back. They were all still watching me. They waved, and I waved. I spent that night in a haystack.

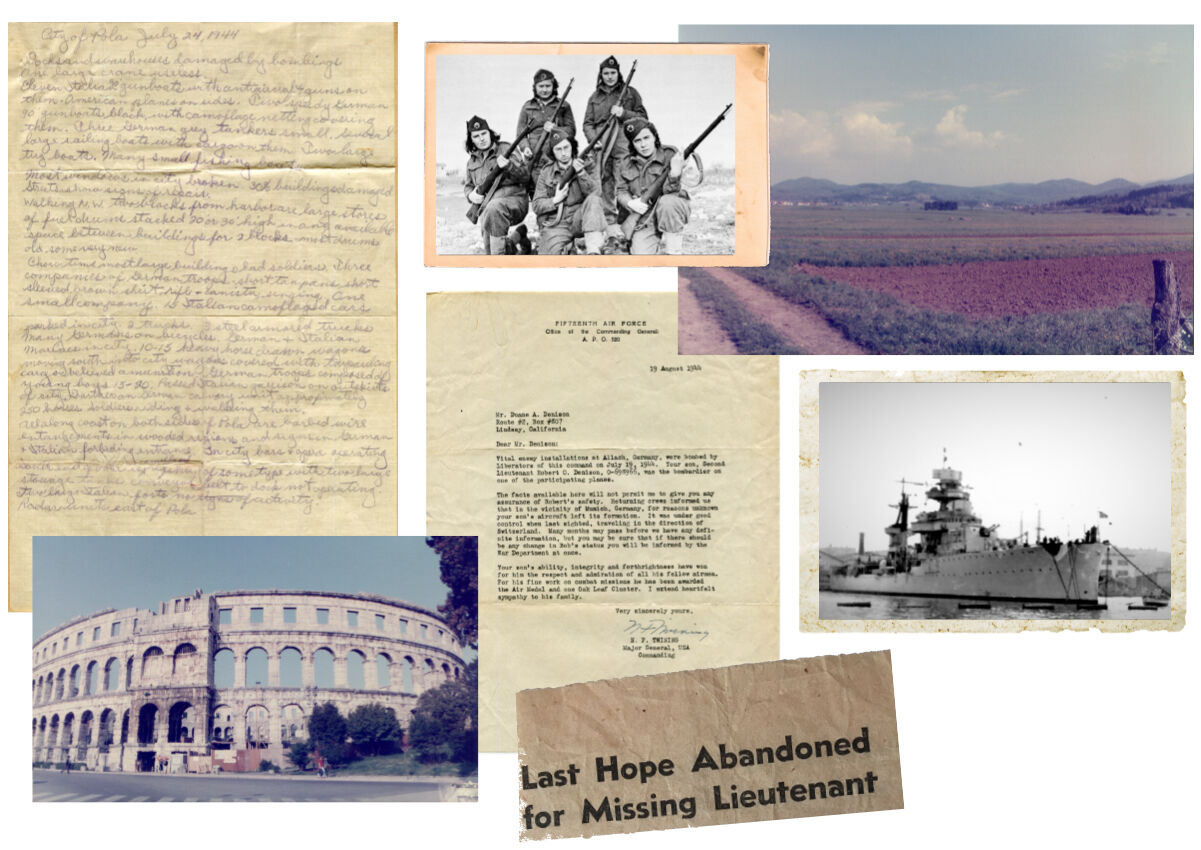

Clockwise from top left: Notes Denison took while in Pula; women of the Yugoslavian Partisans; the Istrian countryside; an Italian cruiser docked in Pula Harbor; a clipping from Denison’s hometown newspaper; Pula Amphitheatre. Center: A letter Denison’s father received while he was missing.

The City and the Colosseum

I set off at sunrise the next day. It was now July 24, and right away I saw a church steeple in the distance. I’d arrived at a major city. The street signs were in Italian, which clued me in a little—but the Italian Empire had also extended deep into Yugoslavia for years. I needed more concrete information.

Wearing a nondescript gray sweatshirt and khaki pants, I must have blended in somewhat with the Italian workforce—lucky for me, since there were so many German soldiers on the sidewalks, I had to walk in the middle of the street.

I went toward the center of town. It had seen a lot of damage, and recently. Radar installations and fuel depots lay in ruins; the aftermath of those British bombers that had awakened me the first night.

I came to the city seaport, where about a dozen torpedo boats were docked one right after the other, flying swastika flags. Painted on the conning tower of each one were red silhouettes of American ships—their kills.

My spirits fell. That really got to me. Those were my people.

I left the seaport in a daze, and there looming overhead, I could’ve sworn, was the Roman Colosseum. I thought, There’s no way I’m in Rome—am I?

I sat on a park bench and watched the German troops marching past those ancient arches. They were all such young men, and for over an hour there was no end to them. Yet performances were still happening in that amphitheater; posters all around it advertised the evening opera.

Finally I shook myself back to my senses. I had to get out of here.

The Wrong Country

On my way out of the city, I saw a girl about my age lean her bicycle against her house as she went in. It was a quieter neighborhood, and I thought, A bicycle would be much faster, and easier on my ankles.

I looked around, saw no one else, and right as I was reaching for the bike, the girl came back outside. My hands were already outstretched, so I had to do something—I mimed asking for food and water.

She gave me a suspicious look, but after a minute she nodded and opened the door. Two other women were inside—her mother and grandmother, I assumed—speaking Italian and preparing lunch. They invited me to join them.

Then the mother asked me, “Chi sei, ragazzo?”

I must’ve felt safer there because they were women. So I answered in English, “I’m an American flyer.”

The mother’s face turned white. She quickly stood up and closed the front door. Hanging on the inside of the door was a fascist uniform.

I was the enemy. But I was also their guest. I could barely breathe; I had no idea what was coming next.

Then the girl asked me in English, “How long until the war is over?”

I said, “I don’t know. ’46, maybe.”

Her family waited for her to translate, and when she did, none of them were happy about it.

“Please, can you help me?” I asked. “I don’t know where I am.”

The girl got up and came back with an atlas. She pointed to Pula, the largest city on the Istrian Peninsula.

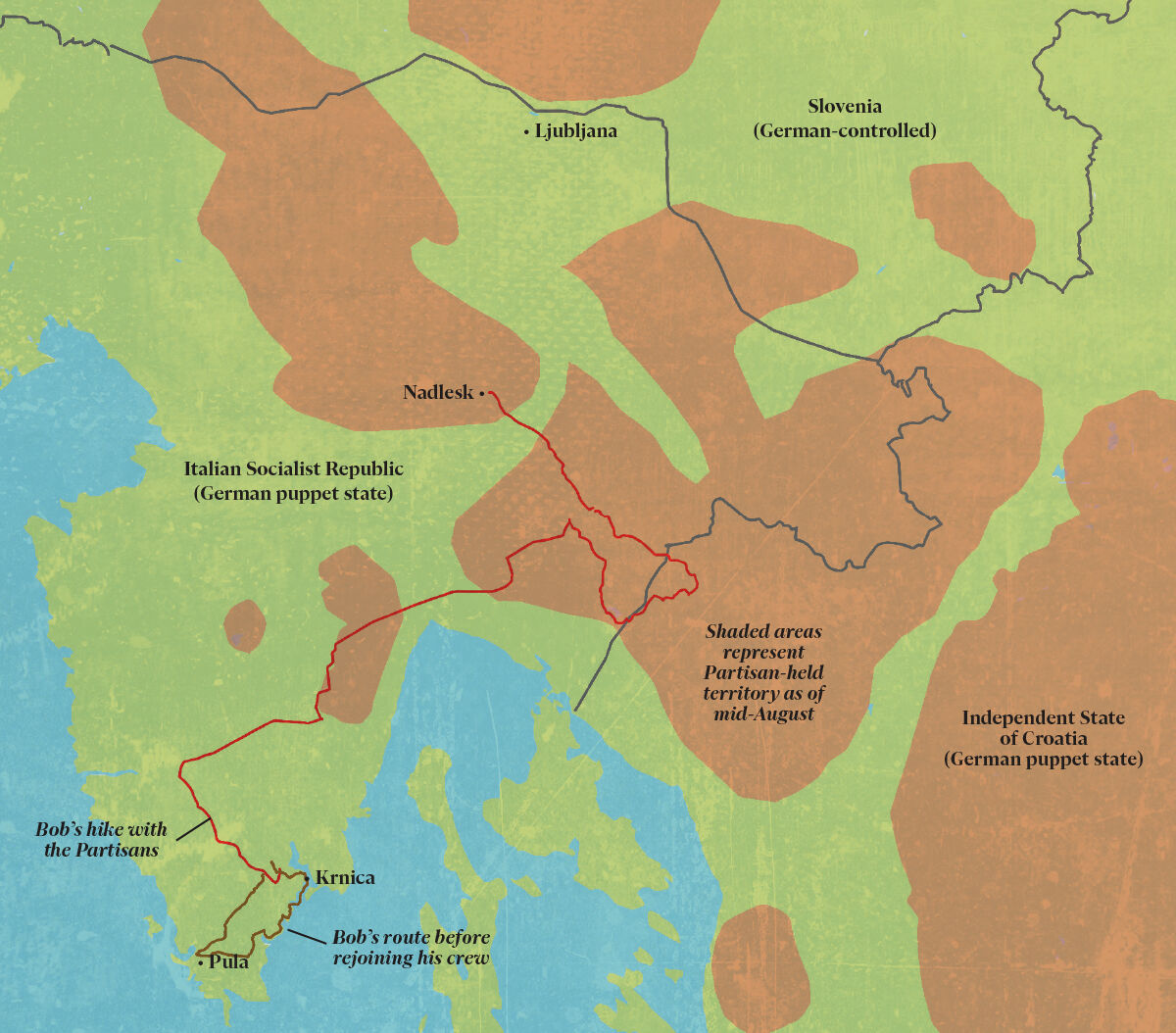

I was shocked. The entire Adriatic Sea lay between me and friendly territory. But then I remembered our briefings on the political situation there. Istria was close to the borders of Croatia and Slovenia. All of this land was still occupied by the Germans, but it had just been reclaimed as united Yugoslavia the previous November by the Communist National Liberation Army, better known as the Partisans. If we landed anywhere in Yugoslavia, we were supposed to seek them out for help.

I asked the girl how I could contact the Partisans. She glanced at her family, then traced a line northeast out of the city. “Follow this road and they will find you.”

Then she closed the atlas and said, “My father will be home soon.”

Veterans Day / Bob’s Hike Map

Nowhere Left to Run

The only way out of Pula was through a gated checkpoint. By the time I saw the German guards, the pedestrian crowd had drawn down to single file, and turning back would only look more suspicious.

My turn. A Wehrmacht officer pointed his finger at me and I stopped. We sized each other up at the same time. I glanced over his immaculate green uniform, his jackboots, jodhpurs, his black-visor cap with the Nazi eagle dead center. He seemed disgusted by my seven-day unwashed clothes—and he squinted at my boots.

Then it hit me. Even the dirt couldn’t hide that my boots were brand-new leather. And the dead giveaway: stamped in large font right across the soles were the initials “U.S.”

The moment stretched on forever. But then he waved me through.

My knees went weak and as soon as I was out of sight I sat down at the side of the road. I didn’t know how I was still alive and walking free.

I followed the road northeast like the girl had told me, and made much faster progress than in the fields. Toward evening I came across a woman chopping wood near a small group of cabins. I greeted her with gestures as I had the others, but she backed away, gripping the ax tighter.

Without thinking, I said, “It’s okay! Me Americano!”

She nodded as if to say, So what? And when I kept advancing, she turned and ran.

The path led up a steep hill and I started up it as quickly as I could. Someone shouted—a crowd of people had come out of the cabins, and three armed soldiers were coming up the road toward me.

I started running, and they started running. If I could just make it over the top of the hill first, they would lose sight of me and I could hide. But I was exhausted, hungry, my ankles in agony; before I knew it they’d all caught up.

There was no way out.

I turned to face the soldiers. One approached me and said, “Tu americano?”

I nodded.

Then he grabbed my shoulders—and kissed both my cheeks. The other two did the same.

At the bottom of the hill, everyone who’d been watching the chase started cheering.

The Partisans had found me.

The Partisans on a long march through the mountains.

Reunited

When I told my story to the person back at the cabins who spoke the most English, he said his comrades had picked up some Americans a few days ago and taken them north, to one of their secret headquarters in the mountains. He offered to take me there.

We set out at dusk and hiked all night long, until finally we arrived at a farmhouse just before dawn. The inside was filled with people hard at work on typewriters, decoding messages by lamplight. My guide checked in with them, and then showed me out back to a tall barn.

Sleeping in the hayloft, above the cows, were all nine of my crewmates safe and sound.

It was a joyous reunion. I couldn’t believe their story, and they couldn’t believe mine. A Partisan happened to be in the field where the copilot and top turret gunner landed, so they were rescued immediately. Six more joined them at their camp by evening, so except for the pilot, who caught up to them the next day, everyone except me had been reunited within four hours of bailing out!

That first night, while I’d been hiding in a ditch next to a German cannon, my crew was drinking wine, eating lettuce and black bread with strawberry jam, and dancing with the locals in Krnica, the very first village I would pass the next morning.

My spirits were soaring at seeing their faces again after an entire week alone. But our journey home was just beginning. The Partisans were taking us north, on a sort of “underground railroad” to the closest friendly airstrip—350 miles across the southeastern Alps, in Slovenia.

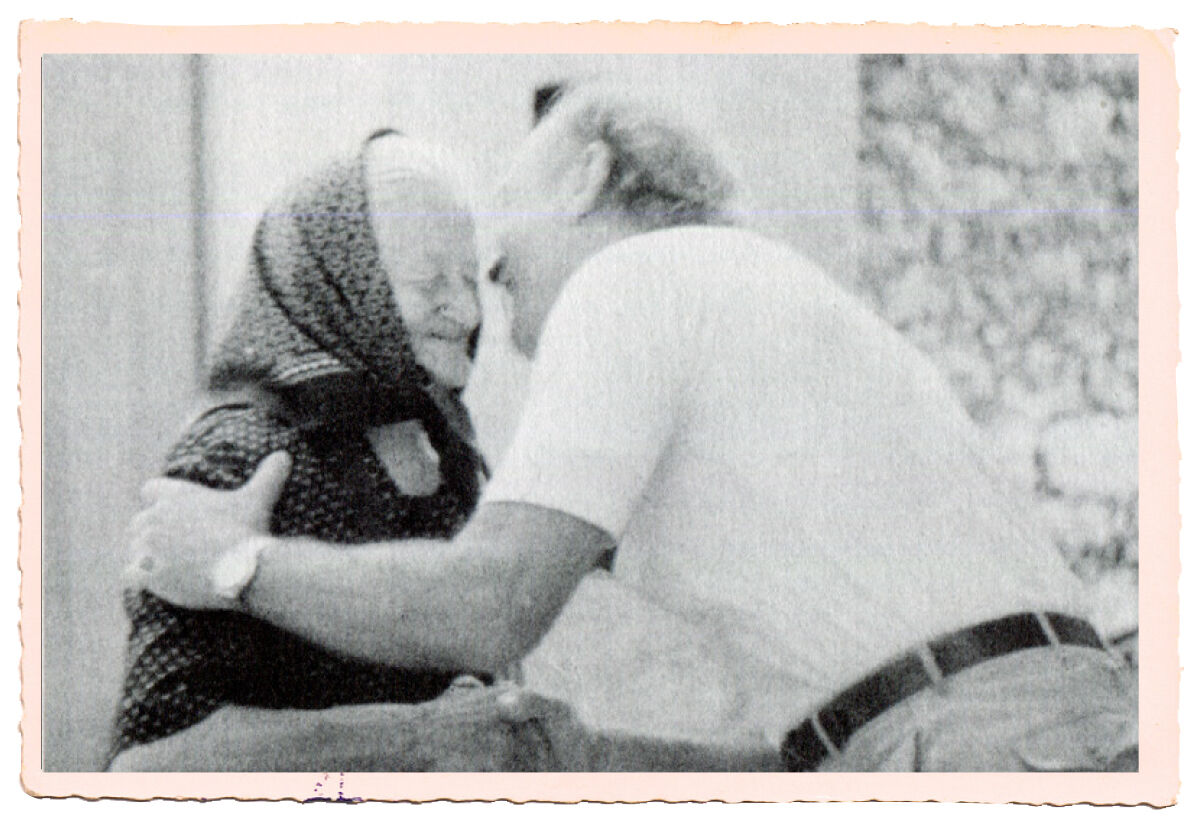

Copilot John Rucigay reunites with one of their rescuers, Marija Benčina, in 1971.

The Long Road to Nadlesk

We had one day to rest. The next evening, the Partisans served beef stew with plum brandy and Charms lollipops. Turns out, they’d tracked down the Little One’s crash site and scavenged everything they could from the wreckage—they were serving us dessert from the survival kits of our own airplane.

From then on it was 11 miles a day at least; the ten of us, plus half as many Partisans who joined or left at certain points to pursue their own missions. Usually that number included a couple civilian women, who carried big flasks of milk from village to village.

We marched, single file, over the mountains every night for almost three weeks, sleeping by day, until we finally entered Slovenia, which was still mostly under German control.

We arrived in a lush valley that the Partisans had recently liberated; they’d driven the Germans back to the head of the valley, just a few miles north. A makeshift landing strip there proved a crucial staging point, and the Partisans suffered heavy losses to maintain control of it.

In the tiny village of Nadlesk, a woman named Marija Benčina let us stay in the hayloft of her barn. Her husband had joined a Slovene anti-communist force, and giving us shelter was her way of subverting his cause. She had two little children, and before we left we gave her all the money we had to support their education.

Other downed Allied troops came into the valley every day, until about 500 of us were all waiting for a spot on the next plane out. A cargo resupply plane came and went on August 19, and another one week later; but so many wounded deserved first priority, we had to wait our turn.

Finally, on August 27, all ten crewmembers of the Little One boarded a British C-47 en route to Southern Italy. We were infested with lice and underweight—I’d lost over 35 pounds—but for the first time in 40 days, we felt safe. Our adventure had come to an end.

John Rucigay, our copilot, was a second-generation Slovene immigrant, so he’d been able to communicate with our rescuers somewhat. He ended up returning decades later to find the village where his parents grew up, and reconnect with the people who saved our lives. Marija Benčina was still living there at her farm. Her children were both well, but her husband never returned from the war.

A Chance Meeting in Yokohama

The story of my service in Europe is filled with unbelievable coincidences, but the greatest of them came years later.

In 1965 I was on R&R in Yokohama, Japan, during the Vietnam War. On our air base there, I met a woman employed in the US Civil Service and invited her to dinner.

I asked her about her German accent. She was about my age, and though she was now an American citizen, she had lived in Munich during the war.

“I bombed Munich during the war,” I admitted.

She didn’t seem surprised. “And I was defending Munich during the war.”

She explained that she’d been a marksman in the German Army; she and two other women were stationed on an anti-aircraft battery. A strange idea popped into my head. “Were you on the guns on July 19, 1944?”

She gave me a funny look. “Yes I was. I remember because we got credit for a possible kill that day.”

“I’ll be god damned.” I burst out laughing. “I think you might’ve shot me down.”

She took another drink. “I bet I did.”

“Aren’t you sorry?” I asked.

“Are you sorry for dropping bombs on my city?”

Well, neither of us would apologize. We were both doing our duty to our country. And now here the two of us were, 21 years later, laughing over drinks and having a great time.

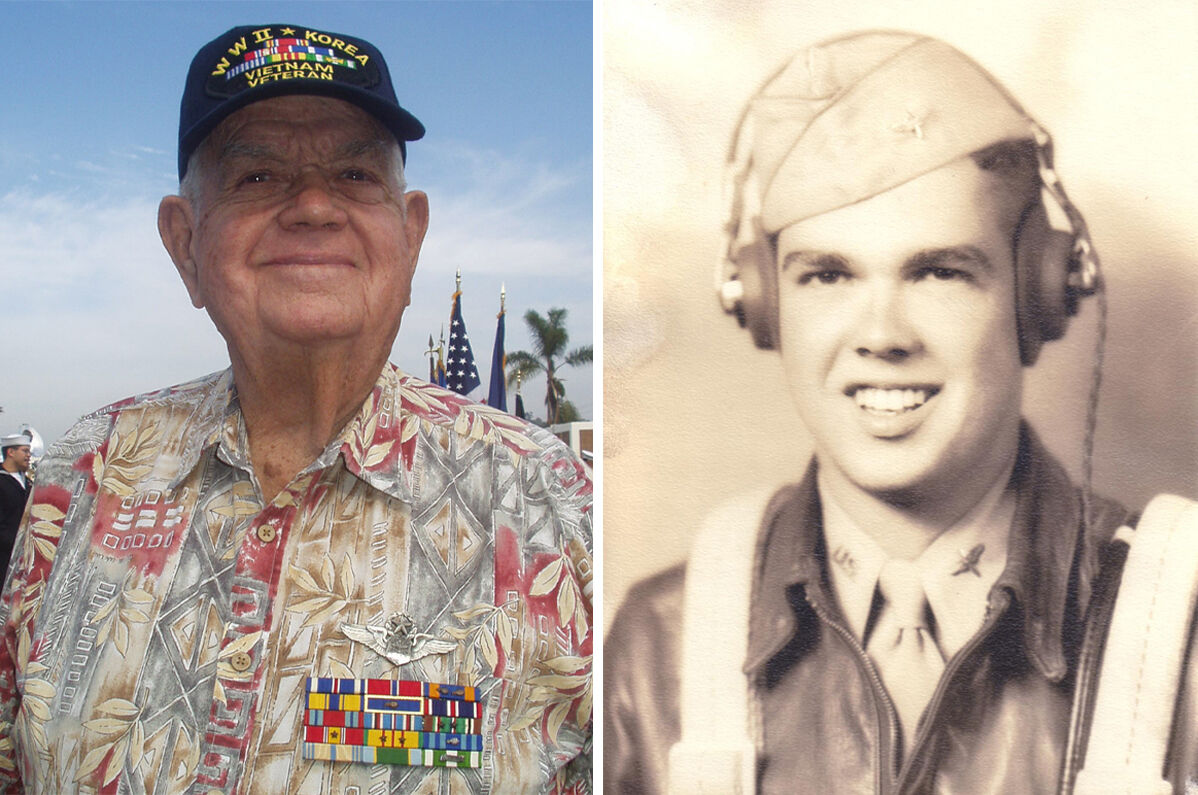

From left: Denison in the 2007 San Diego Veterans Day Parade, and Denison at bombardier school in 1943.

The Distinguished Flying Cross

For our final mission, everyone on my crew was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross—even though we missed our target, destroyed our plane, and had to be rescued by the Partisans. I have always found that ironic. In fact, practically everyone who came to our aid were either Communist soldiers or women (sometimes both) or Black men. Those women helped us at great risk to themselves, because the men in their family had joined the other side.

I think about my experience every single day of the year. The problems we had were amazing, and I can’t help but wonder how we did it. We were all just a bunch of kids. They said go, and we went.

PARTNER CONTENT

Bob Denison retired from the Air Force in 1970 as a lieutenant colonel and lived in San Diego for the rest of his life. When he passed away in 2017, he was the last surviving crewmember of the Little One.