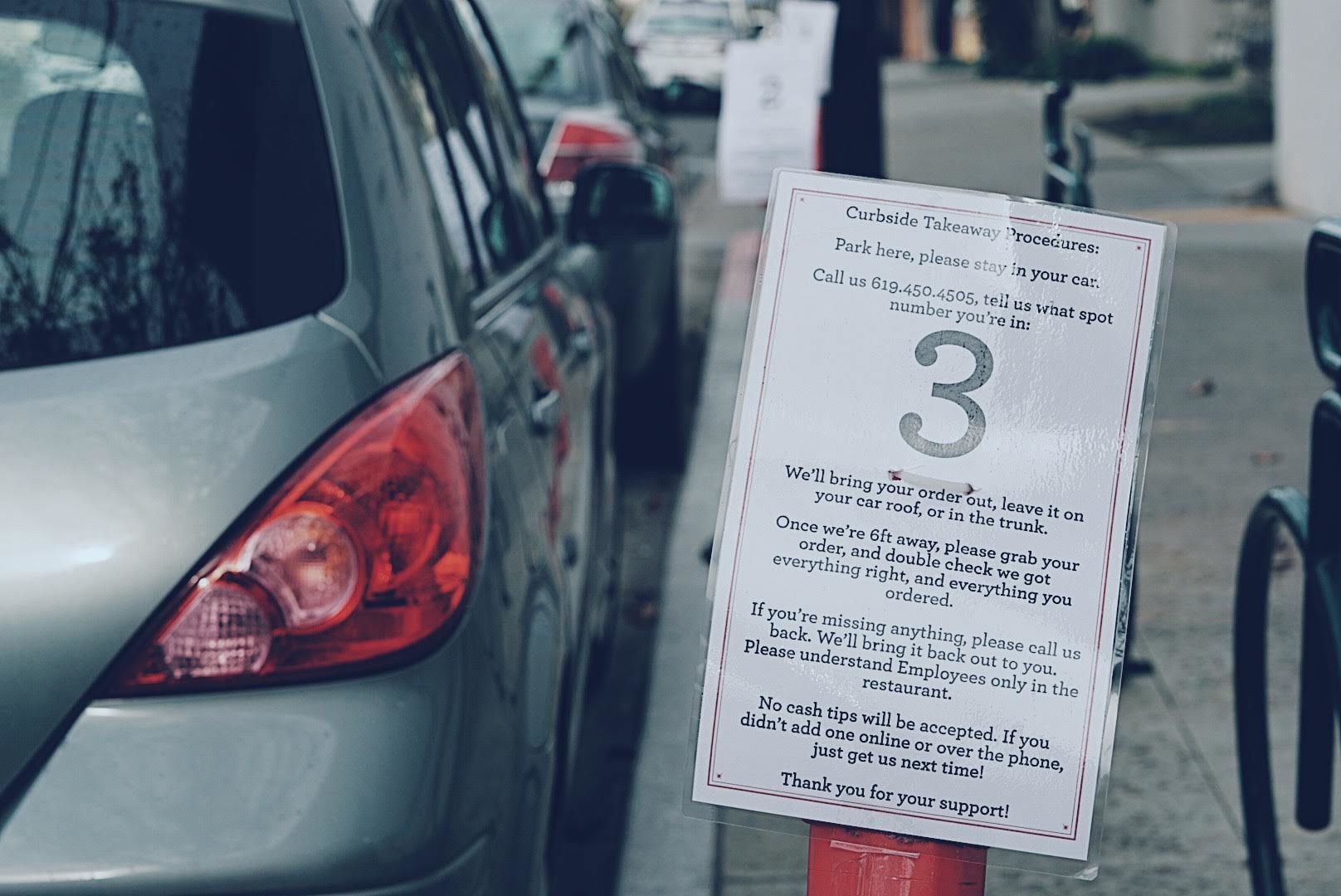

It’s March 21st. I am sitting in my car outside of Tribute Pizza in North Park. I’m a little nervous. I have never been nervous to order a pizza. The restaurant is closed. All restaurants have been ordered closed by the state of California, only allowed to do takeout and delivery. Boxes and boxes of food and relief goods and sanitation supplies are packed against Tribute’s windows. Construction zone barricades on the sidewalk designate pickup zones. I park my CRV. As instructed, I use my cell phone to call them and let them know I’ve arrived. New signs are posted on the windows explaining how to do this. People have to relearn how to order pizza in a pandemic.

A woman emerges. She wears gloves and carries our pizza and a CSA box of veggies from local farmers. We are careful to give her six feet of space. Anyone working serving the public right now is at risk. She gives us two options. She will put our pizza on top of our hood, or in our trunk. She will not hand us the food, and we do not want the food handed to us. We opt for the trunk, though afterward I feel the hood would’ve been safer.

On the drive home, the car smells of hand sanitizer and pizza. Once home, I place everything outside of our front door. I remove all the food from the to-go bag. I won’t allow it in the house where my eight year old is. I take a tube of Clorox wipes, and wipe down all of the containers of food on our porch.

“Is this crazy?” I ask my wife.

Sanitizing the pizza boxes before bringing it into the house.

Photo Credit: Claire Johnson

Italy and Spain and China are on lockdown. California and New York are on lockdown. A third of the country is on lockdown. “Death toll” is a number well wake up to, hospitals are getting crushed with the flood of sick people, healthcare workers are working to the point of exhaustion while exposing themselves to coronavirus every minute of their lifesaving work. For the first time in my life I know what a ventilator is, how many are available in the U.S., and that it’s not enough.

It is definitely crazy. Everything is crazy. Nothing is normal.

Hand sanitizer at the to-go station inside Tribute Pizza.

Photo Credit: Claire Johnson

I carry the food containers into the house, making sure not to put them down on our kitchen counters. I sanitize one free hand, use that hand to grab a clean plate from the cupboard, and dump the contents of the meatballs onto the plate. I do the same with the pizza.

Once all the food is safely on clean plates, I discard the containers. I go to the sink and wash my hands thoroughly for two birthday songs. Finally, we sit down to eat. It is delicious. And yet I’m not totally comfortable doing this. Maybe there is no comfortable way to eat in the pandemic.

Let’s back up to how we got here.

It’s March 8th. I’m at a crowded Mexican restaurant in San Diego taking notes on ceviche. This is my job. I take it very seriously. I’m unaware how wildly luxurious it will be a week from now to think about ceviche. I’m unaware how wildly free it was to be in a crowded restaurant and not worry about endangering a healthcare worker or a grandparent or humanity. Beyond washing our hands every hour or so, life is relatively normal. There are many birthday parties happening around us.

It’s March 9th. In four days, I’m scheduled to fly to the Midwest to film a TV show about restaurants. But the country’s starting to quiver a little bit. My wife and I decide to keep our two-day trip to the mountains. It’s important. I’m going to be gone for weeks. I need her to remember who I am.

It’s March 10th. I wake up in Big Bear to a text from my co-host: “I’m a little nervous.” She’s not a nervous type. Five days earlier I had asked her if she was concerned and she said she would kick coronavirus’s ass. I believed her. We laughed it off, a tad uneasily.

I get on a call with our producers to gauge their concern. They just don’t know. Nobody knows. We’re not epidemiologists. Just average people binging on the news cycle, trying to not be on the wrong side of history. At that point it was still valid to ask, “Is it bad enough to cancel things and ruin people’s lives economically?” Our TV show helps restaurants by telling their stories. At this point they are struggling because the virus has reduced customers to a trickle, and their people—dishwashers, cooks, servers, bussers, bartenders, owners, suppliers—need help. Four hours after that call, the WHO declares coronavirus a pandemic. We cancel our flights, postpone the show. It feels terrible and right, but even then we’re not sure.

Construction cones denote where to park for curbside pickup.

Photo Credit: Claire Johnson

It’s March 11th. We are now sure. The NCAA basketball championships are canceled, along with the NBA, MLB, NHL, Broadway plays, St. Patrick’s Day parades, South by Southwest and Coachella. Elementary schools close, college campuses shutter. Then they turn off whole cities, entire countries. Tom Hanks contracts COVID-19, which feels like a personal attack on America. Then the guy from James Bond movies. An NBA player gets it. In a year that “cancel culture” became a national exercise, coronavirus cancels culture.

The media flashes images of people standing in long lines to buy guns. People joke that it’s not like we can shoot coronavirus. It isn’t a skeet flung into the air off the side of a cruise ship. But we all know the guns aren’t for the virus. Nothing forms lines at the gun shop quite like fear.

Overnight, two-thirds of my income is “postponed.” It’s harder to play with your eight year-old when you know existentially bad news that affects the both of you. You make her a fort with a little less gusto, no matter how hard you try to manufacture joy.

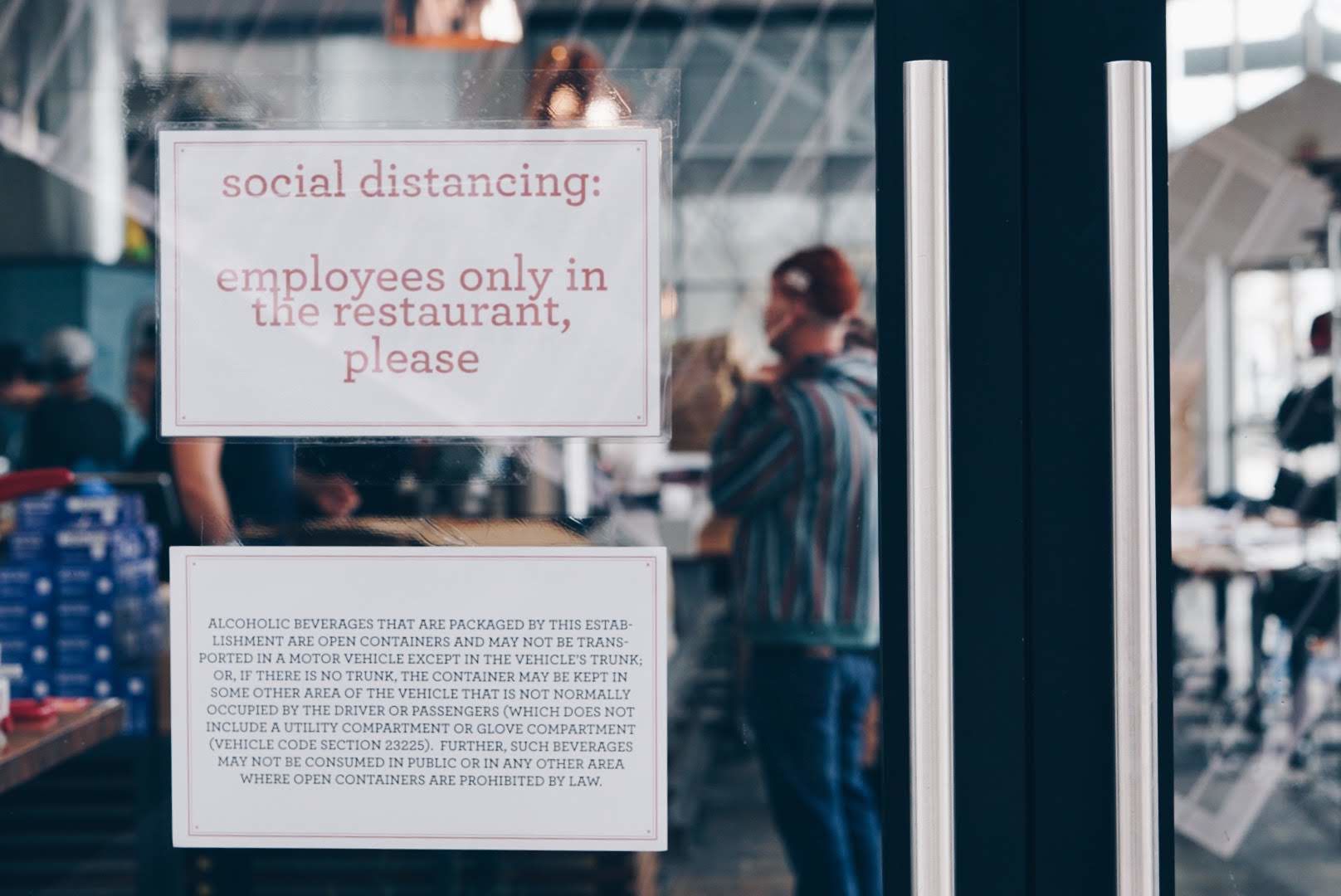

Workers inside Tribute monitor the customers arriving.

Photo Credit: Claire Johnson

Corona is a social virus. “Social distancing” becomes the global slogan, that awful refrain, as common in conversations as “um.” The tragic realization is that this means the people who create social spaces have to fall on the sword. Restaurants’ and bars’ entire purpose is to shrink the ever-increasing space between us. To bring people together, within feet or inches, very much on purpose. Recently, as tech has isolated a lot of us, that function seemed especially important and vital. And now, the thing that makes them vital and special is making them life-threatening.

It’s still March 11. A chart begins to circulate from online reservation platform, OpenTable. The numbers for the San Diego market for the beginning of the month are green, showing an increase in business. Then on March 8th the numbers began to sink: -7%. March 9th it was negative 13 percent. Then 31 percent. On March 11, there is a small uptick of three percent. People heard their cries of help, and they showed up to eat and drink and support the small business owners and their employees. And then, March 12th, hell breaks loose. Restaurant business nosedives, down 43%. For an industry that exists week-to-week on tiny profit margins (the industry standard is 3-5%), this is the point of no-return. It’s not just unsustainable, it’s fatal.

Tribute makes a real good pizza. Owner Matt Lyons got advice from pizza legend, Chris Bianco.

Photo Credit: Claire Johnson

The message from restaurants is that they are being extraordinarily safe. And it’s true, part of a restaurant’s daily task is preventing pathogens from getting their customers sick. For decades, they have been governed and inspected by health agencies. Sure, there are some that look like a dumpster fire, but most of the good ones are cleaner than your own.

Still, restaurants poise a problem—a crowd, touching common items (menus, condiments, tables, chairs, credit card machines, etc.). So they begin taking drastic measures, removing tables to make sure there is the recommended six-foot safety distance, removing condiments and menus, increasing the concentration in their sanitizing solvents, handing out hand sanitizer with orders. Desperate measures for desperate times.

I do hundreds of pages of research, speak with a friend who’s an epidemiologist. I try to determine whether professionals are saying it’s safe to dine out and help these people. Most of the experts say as long as you’re safe and not in the at-risk category, it is. The L.A. Times critic Peter Meehan writes a story that basically says it’s safe. The piece seems a tad cavalier, but not tone deaf. I try strike a middle ground, relaying experts who say it’s safe if you’re not in the at-risk category and take precautions.

Within 48 hours, that all changes. I have to adjust the story, relay the CDC’s recommendations that everyone avoid restaurants. (Meehan will do the same to his story). On my personal social media, I post a long admission that after all the research I believe restaurants need to shut down. I feel like I’ve betrayed the people in my industry. But the facts about coronavirus are too dire.

It’s March 15. Chef Brian Malarkey calls me to say he’s closing all of his restaurants, the first major closures in San Diego. He lets his staff shop in the walk-in refrigerator, taking home duck and lamb and eggs and cheese and produce. It’s a nice gesture no one wants. But Malarkey is confident every restaurant will be ordered closed soon. Calling it early gives his people a jump on the unemployment line, which will buckle under the strain in days to come.

The night before they close, customers enjoy one last meal, leaving generous tips to help the staff. One man tips $700. At Garden Kitchen in Rolando, a man walks in and buys a $750 gift certificate and says he’ll see them when this is over. At Little Lion, regular people who don’t appear to be wealthy (a description from the owner) are handing out $200 tips.

It’s March 16. The County of San Diego orders all bars closed, and closes all dine-in spaces at restaurants. They are now allowed to do only takeout and delivery. For many restaurants, this is their financial apocalypse. My email inbox is flooded with hundreds of messages from restaurant owners small and large, begging for help. I begin frantically posting their messages on social media. I post stories on San Diego Magazine’s website.

Nationwide rallying cries go out on social media, urging people to buy gift certificates from the restaurants, buy their merchandise, do anything they can to help them. The industry’s low-income employees flood the unemployment lines. GoFundMe pages are set up for them. Some restaurants dedicate a portion of sales to them. Some restaurant owners simply can’t. There’s a myth that every restaurant owner is wealthy, will just go home and lay by their pools until this subsides. But anyone who knows this industry knows that’s the cruelest lie, that most restaurant owners are small business owners who are only one bad month or two away from closing.

Every morning, I wake up to dozens of messages asking for help. There are just too many. The heartbreaking stories are just coming too fast. I feel a crushing guilt for not being able to help them all. At the same time, it feels insanely unfair for me to choose who to help. The process of interviewing them, writing a story, editing that story, fact checking, getting images, and posting that story is far too slow. My work rapidly morphs from longform story writing to informational triage. I’m just trying to relay SOS messages as quickly as possible.

In the middle of this, my eight year old daughter sits on the couch. With county schools canceled, she’s home all day with my wife and I. She needs love and attention and schooling and food. Normally my parents could help take care of her, but they are over age 70 and all have underlying medical conditions, so we can’t risk it. With most restaurants closed, my wife and I find ourselves continually loading up on groceries, cooking three meals a day, doing dishes, so many dishes, trying to work in the moments between.

Tribute offers CSA boxes now to get local food to its customers and help local farmers.

Photo Credit: Claire Johnson

So I take a few days to develop a new system. I start doing Instagram Live interviews with people in the food and drink community. The videos put a human face to the disaster. I’m able to use my social media channels to connect these people directly with my followers—a network of about 60,000 people. That’s not huge, but it helps. My followers can see into their kitchens, see what efforts these people are making to ensure their food setup is safe and responsible. They’re able to see these people’s eyes. The community responds to it.

In the beginning, to be fair, I refuse to choose who to help. I just let anyone into my Instagram videos to tell their story. My wife, who’s also in media, is nervous about this. She says it’s vaguely irresponsible. I push back at her. I tell her people need help, this is the fastest and most democratic process. We nearly argue.

“What if someone joins in and is naked?” she asks. “What if someone uses this platform to scam people?”

God, she’s right. Sad as it is, this is irresponsible. I have to verify these people. I have to choose who to help. It’s brutal.

So I start setting up scheduled times with various local food and drink people. I want to be inclusive—include people from every neighborhood, every nationality, mom and pops, people really in need. But even the big companies like Specialty Produce need help, because what they employ hundreds of people.

The live Instagram interviews are also a little too long. People have a lot to say, so much chaos to work through. I know as a journalist and writer and TV person that viewers don’t have the attention span for this. The videos need to be shorter. But any shorter, and they lose humanity.

At the same time, a large portion of the planet starts to quarantine, shelter in place. Everyone on the globe, it seems, begins to go live on Instagram. The channel becomes clogged with musicians, artists, employees, writers, journalists, TV people, everyone—isolated and trying to connect with an audience who can help. It’s like an open-source crisis hotline. In doing so, the app becomes its own pandemic. Jokes start circulating making fun of everyone doing Instagram Live.

And yet, still, we do. There are only so many ways to help, and this seems the fastest, the most immediate.

Restaurants and food people and their customers are doing amazing, hopeful things. Some of them are turning their restaurants into general stores or bodegas, selling essential goods to locals who can’t get to the grocery store, or get there and find the grocery store empty. Local company Skrewball Whiskey pledges up to $500,000 to U.S. bartenders out of work. Most restaurants that have stayed open for delivery and takeout are not making money. Sales do help keep the lights on, but most of them are doing it as a community service. There’s a reason governor Gavin Newsom included them as “essential businesses” that could stay open. Because adding food insecurity to a pandemic is never a good idea. Grocery stores can only do so much.

The toughest thing is that many restaurants only make money at the bar. Food is often a loss leader. And with no one ordering bottles of wine or sitting at their happy hour, restaurants can’t make that money. The ABC makes an emergency change to its laws, allowing any restaurant with a license to serve booze to-go as with food. Restaurants start selling Negronis out the front door. It helps a little.

Restaurants can now serve cocktails to go if you’re also ordering food.

Photo Credit: Claire Johnson

But it’s not enough. None of this will likely be enough. Some restaurants will be able to weather it. So, so many of them will not. Small business owners will be financially ruined without help. But help from where? The landlords? Can we expect them to take the financial burden? From banks? From the government? If we’re going to save these people, it’s going to have to be a combination of them all.

And so I sit here wiping a Tribute Pizza box with a hand sanitizer, as my phone explodes with messages from food and drink people, from my mom wondering if she’s allowed to have her housecleaner still come to her house (absolutely not, pay the cleaner to not come for a month), from friends checking in on me, from news alerts about COVID, from friends with explosive political opinions and memes to help distract us for a second.

When you arrive at Tribute, you call the restaurant and they’ll walk your food outside.

Photo Credit: Claire Johnson

I sit down on the couch, eyes puffy, exhausted. My daughter tries to keep quiet at the dining room table doing her homework. My wife takes a conference call in her office, trying to keep us financially afloat. I briefly think about the broccoli in the fridge that has to be cooked today before it goes bad, about my need to Google signs an eight year old is depressed, about how to keep your marriage solid during a quarantine.

I face the tripod with my phone loaded to Instagram. I push “Go Live.” I see another tired face on the other end of the video, a restaurateur or a small business owner. We say a tired hello and this goes on.

New signage in the window at Tribute explain pizza in a time of coronavirus.

Photo Credit: Claire Johnson

The good news is that people are rallying behind these small business owners and their employees. They’re buying gift certificates. They’re buying merch. Restaurants have never been about food. They’re about people. And now the people need to be about restaurants.

This virus will have a lasting, unimaginable effect on restaurant life and our culture long after the virus itself has gone dormant. I don’t really know what that will look like. No one does. In the meantime, I’ll continue telling the people’s stories here and on Instagram Live.

PARTNER CONTENT

And as long as the CDC says it’s safe and the restaurants remain open for takeout and delivery, they will be part of how we all get through this.

Tribute Pizza, 3077 North Park Way.