If the marches, protests, and rallies weren’t evidence enough, 2017 has become the Year of the Woman. From local and federal government to startups and sports, the focus has shifted to the female leaders blazing trails and shattering records while they’re at it. They don’t take “no” for an answer; they persist.

Our city is no exception. San Diego is teeming with female icons in careers as varied as science and architecture. Here, we shine a spotlight on four local women who’ve endured it all—male-dominated industries, cancer, injuries, extreme temperatures, and worse—and come out on top. Badass, indeed.

Edie Littlefield Sundby

The first person in history to hike the 1,600-mile El Camino Real Mission Trail

4 San Diego Women Who Are the Definition of Badass

Edie Littlefield Sundby was arrogantly healthy. She ate organic food, practiced yoga, loved being outside—and had not been to a primary care doctor in over twenty years. Then in 2007, at 55 years old, she was diagnosed with stage 4 gall bladder cancer—a rare form that’s almost impossible to detect in its early stages, before it spreads to other organs—and given three months to live.

What do you do when life throws you a serious, life-changing, possibly life-ending curveball? You either give up, or you fight. Despite her odds of survival being less than one percent, Sundby chose to fight.

“I was terrified, and fear is a great motivator,” she says.

Today, 10 years after her diagnosis, Sundby has become the first person in history to hike the entire 1,600-mile El Camino Real Mission Trail from Loreto, Mexico to Sonoma, California.

Despite the cancer, which has returned aggressively several times, she is full of energy and determination. It’s hard to imagine that the smiling, immaculately dressed, soft-spoken woman sitting in front of me has not only survived 79 rounds of chemo and four major surgeries—including the removal of her right lung—but also traversed some of the most inhospitable terrain on earth, walking in the footsteps of St. Junípero Serra on the Old Mission Trail in Baja California. Calling it a trail might be overly generous, though.

“It’s not a concrete jungle,” Sundby says. “It’s a mountain jungle, a cactus jungle, a desert jungle—sometimes all in the same day.” Big stretches of the Mexican leg of her journey are largely inaccessible by foot and must be traveled by mule.

In her new book, The Mission Walker, she relives part of the trail known as El Paraíso—a 2,000-foot drop straight down the side of a mountain, completely covered in cactus. “Mules don’t want to go down it, no one wants to go, but you have no choice,” she says. “It’s one of those situations when you have an Indiana Jones moment; it’s harder to turn back than it is to plow through.”

But she wouldn’t hesitate to do it again. “It’s those moments in life that thrill us, that stir something within us, that really bring us close to God.” She walks because it makes her feel alive.

“I believe we’re spiritual beings in a physical existence. And when something life-threatening happens to your physical existence, what’s going to kill you, quicker than killing you physically, is something that kills your spirit,” she says. “As long as your spirit is in control, as long as your will and belief are engaged, whether you live or you die, you conquer. You don’t let it kill your spirit. In order not to let it kill my spirit, I had to engage.”

Sundby grew up in the 1950s on an Oklahoma cotton farm without electricity or running water, the second youngest of twelve. She put herself through college by selling bibles door-to-door, and later went on to become one of the first female sales executives at IBM.

“IBM was an incredible place to work. It was all a meritocracy, especially in sales,” she says, comparing the experience to when she was a kid, working to earn her own money. “Then, it was all about how many doors you knocked on, how many newspapers you were able to sell. It wasn’t how you looked, it wasn’t your sex. It was just: Are you willing to sit out in that corner in the rain and were you able to knock on a few more doors?”

In other words, she is not the kind of person to take no for an answer. So when surgeons and specialists told her surgery was too dangerous, she found a different surgeon. When she was told not to go down to Mexico, she went anyway.

“That’s the nice thing about cancer,” she says. “You don’t screw around. You just do it. You don’t look for perfect.”

Vivian Lee

Ultramarathoner who’s raced at the North Pole and in the Sahara

4 San Diego Women Who Are the Definition of Badass

Two years ago, Vivian Lee had never run a marathon. She didn’t even particularly like running. Then her friend needed a half marathon relay partner, and Lee thought to herself, Six miles… maybe it’s not that bad? Those six miles quickly turned into a half marathon, a full, and an ultramarathon. Today, the 46-year-old Encinitas-based software engineer is only two races away from a Grand Slam—one marathon in each of the seven continents, plus the North Pole.

For most people attempting a Grand Slam, the North Pole Marathon is the last on their list. It’s the most difficult to get to, and has arguably the toughest running conditions. Lee, on the other hand, started at the North Pole, and it’s what got her hooked on extreme marathons.

Lee, who is originally from Beijing and came to the US in 1991, is an avid traveler—at ages 10 and 13, her children have already been to six continents with their parents. When the North Pole Marathon happened to show up in one of her Google searches, she instantly emailed the race director to sign up. At that time she had never actually run a full marathon.

To practice, she started scheduling family vacations to cold-climate destinations, like Denver and Quebec. And while her family was skiing in Mammoth, she was running.

The North Pole is not for the faint of heart. On race day it was minus 22 degrees, there were cracks in the ice runway that kept delaying the event, and once it began, she had to stop several times to change her face mask before it froze over.

“After the first stop I waited too long to change it again, and I had to wait for it to thaw so I could take it off,” she says.

After the North Pole, Lee quickly knocked out a marathon in Australia, one in Europe, and one in southeast China for the Asian leg of the Grand Slam. When I met with her in June, she was just weeks out from running an Inca Trail Marathon in Peru—where altitudes range from 8,000 to 13,779 feet.

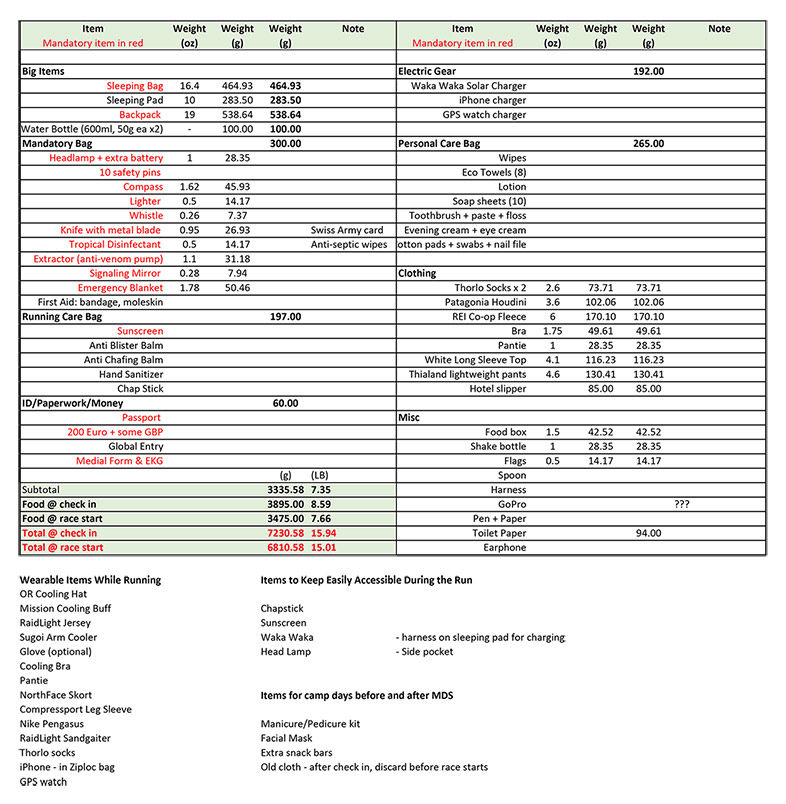

It’s a lot easier finding a marathon to run in Europe or North America than in South America or Africa. So for the African leg, Vivian ended up picking the Marathon des Sables. Held each year in April, it’s a six-day, 156-mile ultramarathon through the Sahara Desert that is known as “the toughest footrace on earth.” The distance adds up to about one marathon a day for six days straight, and participants run through sand in scorching heat with temperatures of up to 120 degrees, carrying a week’s worth of supplies on their backs, including food, clothes, and sleeping bags.

“It took tons of preparation,” Lee says. “On the weekends I was doing back-to-back half marathons or longer for two months.” And while her family and friends were sitting down with a steak and a glass of wine, Lee was on the freeze-dried food diet, or doing detailed measurements of how much toothpaste is needed for a week. (Exactly one ounce, it turns out.)

“The food you carry, not only does it have to be light, it has to have enough calories for you to even check in,” she says. “They require 2,000 calories a day. If you don’t have that, you won’t be able to start the race. And 2,000 calories is probably a little over the metabolism rate to keep you alive, but definitely not enough. You will run into a calorie deficit.”

Other risks when running the Marathon des Sables? Dehydration, kidney failure, heat exhaustion, swollen feet, infected blisters—there’s a reason “corpse repatriation” insurance is included in the registration fee. Every morning, the race kicks off with AC/DC’s “Highway to Hell” to set the tone for what the runners are about to endure. So why would anyone voluntarily put themselves through this?

For Lee, it’s about pushing her own limits. Running the North Pole Marathon was a true test of her abilities. “It was not enough to kill me, and I knew I was not at my limit. I knew I could go a little further,” she says. Her running also raises money for the orphans of the Niños de Fe Children’s Home, which is a major motivation as well.

“When things were getting hard, I would say to myself, ‘If you quit, how do you tell those kids?’” she says. “When things get tough, that’s what gives me the power to keep going.”

4 San Diego Women Who Are the Definition of Badass

vivilee

Chrissie Beavis

X Games gold medalist, pro rally driver, designer, and fabricator

4 San Diego Women Who Are the Definition of Badass

Being a total badass seems to come naturally to Chrissie Beavis. The 36-year-old City Heights resident has been called one of the most unstoppable women in action sports: an X Games gold medalist, a professional rally driver and navigator, and the head judge and rally master of the all-female, San Diego–based Rebelle Rally. She also coaches women who want to learn rally driving and navigating.

It’s a heavily male-dominated industry—but for Beavis, that has never been an obstacle. If anything, she says, her experience has been the exact opposite: “I probably get more opportunities because I’m a woman. Because it’s something different, it’s the underdog thing.”

Her mother, Paula Gibeault, started rallying in the 1970s, so she was basically born into the racing lifestyle. The fact that other women might not have the confidence to get into rallying never even occurred to her.

“I didn’t realize other women didn’t do that,” she says, “didn’t have that confidence that I have because of my mom. My mom’s always been a super-confident, competent person in a man’s world, in the rallying world. So it kind of blew me away that other people don’t have that. ‘What do you mean, why wouldn’t you just go and race?’”

For Beavis, this mind-set has led her to an impressive list of accomplishments: Codriving with top names like Tanner Foust and Travis Pastrana, winning X Games gold and silver medals, and successfully racing her own rally car as a driver.

When she’s not rallying, coaching, doing on-camera driving for TV and movies, or working out the technical aspects of the Rebelle Rally, Beavis is running her own architectural design and fabrication business. She has a degree in architecture, but during a college internship, she realized she wasn’t cut out for working at a traditional firm.

“You just sit in front of a computer all day long, that’s all you do,” she says. “You’re drafting, hardly designing anything, and I realized I wasn’t going to be able to stand that.”

Instead, she started her own business almost right out of college. Today, she designs and fabricates custom solutions for restaurants, boutiques, and private residences. She’s also designed a few homes. “I did a full residence for a friend of mine in Newport, which was really fun,” she says. “We had a contractor build all the main stuff and then I got to build all the custom parts.”

Beavis and her husband—Matthew Johnson, also a professional rally driver—recently bought a two-unit fixer-upper in City Heights that they completely remodeled using mainly reclaimed, sustainable materials.

While architecture and rally racing might not sound like a logical fit, she says they have a lot in common.

“Being a trained architect, I know how to draw and I know angles and lines, and when you’re plotting on the maps, it’s important to be very precise.”

Most of her fabrication clients are women, and in the last few years she’s started focusing on helping other women who are finding their place in racing, as well. She was introduced to the Gazelle Rally through Emily Miller, a fellow racer and the brains behind Rebelle Rally. The Gazelle Rally, or Rallye Aïcha des Gazelles, is an annual nine-day, women-only off-road navigation rally in Morocco. Teams of two women—a driver and a navigator—drive 2,500 kilometers through the Sahara Desert in search of checkpoints, using only topographic maps and a compass. It’s a physically and mentally challenging race, but Beavis, who has done it three times (and won once), says it’s an experience that blew her mind.

“The idea of an all-women rally is just so amazing and so empowering,” she says. “We don’t realize as women how much we’re socially conditioned to rely on other people, even if it’s other women. So when you’re out there really relying on yourself, and you have that confidence to rely on yourself, that’s really something that changes people’s lives. I love that.”

Brittney Reese

Olympic gold medalist and track coach at Mesa College

4 San Diego Women Who Are the Definition of Badass

“We don’t quit.” Those three words from her grandfather ended up shaping Brittney Reese’s entire future. In the seventh grade she wanted to quit running, but her mother and grandfather had none of it. So she ended up sticking it out, and in 2008, she made it onto the US Olympic team as a long jumper. Reese went to Beijing that year prepared to come home with a medal, but ended up placing fifth.

“I was devastated. I thought I was at least going to go home with something, and I didn’t get the opportunity,” she says. “So I made a promise to myself that I would never get left off a podium again.”

With very few exceptions, that’s a promise the 30-year-old Chula Vista resident has been able to keep. She won her first IAAF World Championship in 2009, and followed it up with wins in 2010, 2011, and 2012. But she was still missing that crowning achievement.

Then, at London 2012, she jumped 7.12 meters and brought home the gold. Reese describes the experience as a burden lifted off her back. “I had worked so hard, so when I finally got it, I couldn’t do anything but cry.”

Since then, Reese has added two more World Championship titles and an Olympic silver. She’s grown so accustomed to winning that now, anything less than gold feels like a defeat. In 2013, she faced her biggest challenge yet: She injured her hip while competing, but no one could tell her what the issue was. Despite the pain, she pulled herself together and won that year’s World Championships in Moscow. But the problems with her hip didn’t subside.

“I took a month off, and the second week back into training, it started right back up,” she says. “I realized something was seriously wrong.”

When another round of tests showed that she had a torn hip labrum, Reese opted for surgery. She was out for three months, working hard in rehab while growing increasingly tired of being hurt. “I kind of rushed myself to get back and didn’t take the time out that I really needed, and ended up still not fully healed,” she says. The next year she went back for another World Championship title, but her body wasn’t ready yet.

“I started having back spasms, to where I couldn’t walk,” she recalls. “It was devastating. That was the first time in my life that I didn’t make a World Championship final.” She ended up placing 24th, and had to fight both mentally and physically to get herself back to the top.

The next year, in 2016, Reese took home another World Championship title, along with a silver at the Rio de Janeiro Olympics.

“I told myself that I needed to lose,” she says, “because I’d been winning so much, I had forgotten how it felt to actually really lose.” It was a good lesson not only for her, but also for her 9-year-old son, Alex.

Reese grew up with Alex’s biological mother in Gulfport, Mississippi, and has been close to him his whole life. She officially adopted him a few years ago, and now she’s showing him the value of hard work.

“I like to push him and let him understand that things in life don’t come free; you’ve got to work for things.”

Despite having lived in San Diego for the past five years and working as a track coach at Mesa College, Reese is still very much an active advocate of her community back home. In 2011, she famously donated 100 Thanksgiving turkeys to various homeless and religious organizations in her hometown. She also has a scholarship program, and this fall she’s going back home to run her second annual speed and agility clinic for kids in the community.

“I try to do a lot to get the kids involved and just show the community that I’m not forgetting about where I came from,” she says. “For me to be able to represent my country and be able to bring something home, especially the Olympic gold medal, back to where I’m from in Mississippi—we don’t see that every day.”

Today, Reese holds the record in the women’s indoor long jump. As of press time, she also has the women’s best jump in the world for 2017. “I’m having a decent season,” she says, smiling.

PARTNER CONTENT

4 San Diego Women Who Are the Definition of Badass