Telling Stories Through Pictures

How much of a tale can drawings alone convey? Brian Selznick would say, quite a lot. His books attest that pictures can tell a complete story—and words are not always needed.

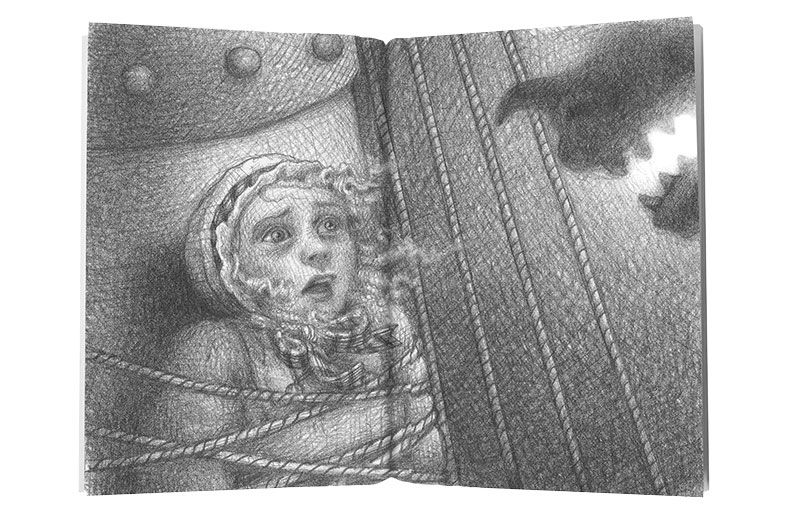

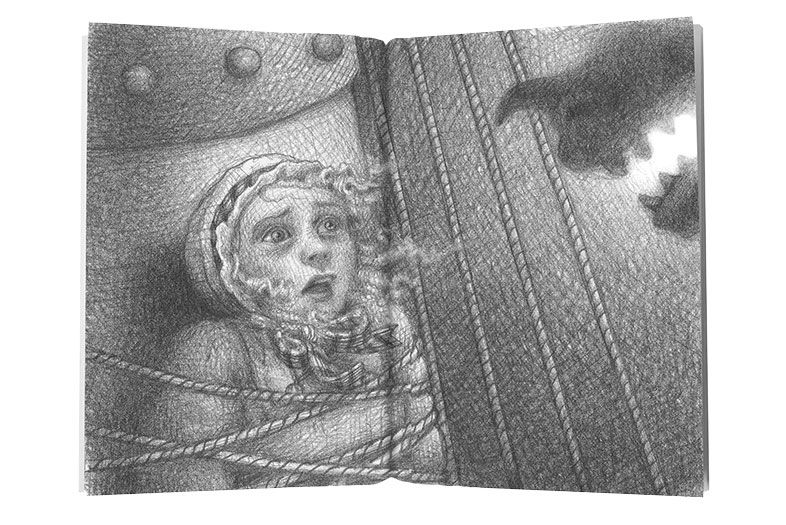

The La Jolla–based author was already a well-respected and well-known writer and illustrator of books for young readers when he created a book that eluded any conventional category. The Invention of Hugo Cabret, published in 2007, is equal parts drawings and text. But the images aren’t employed as illustrations. Nor are they used in the way that graphic novelists arrange images. One picture segues into the other as you turn the pages of Selznick’s novel, with long sequences telling the story of a boy who lives in a Paris train station and helps his uncle service the clocks.

Hugo Cabret became a best seller, won a prestigious Caldecott Medal, and was made into the widely acclaimed 2012 film Hugo directed by Martin Scorsese.

“It was the hardest book I ever wrote,” Selznick says of Hugo Cabret. But he felt the same way about Wonderstruck, which was equally acclaimed and popular when it debuted in 2011. True to form, he is calling his new novel, The Marvels, out September 15, his most difficult undertaking.

“Every book is the hardest one to do, until the next one comes along,” he admits.

The Marvels tells the story of five generations in a celebrated British family of actors, beginning in 1766 with Billy Marvel, via 400 pages of pictures. Then, using only text for 200-plus pages, Selznick switches to the tale of a teenager, Joseph, who flees his boarding school and takes up residence with an uncle he barely knows, in a home that turns out to contain its own marvels. (And that house in the second story, we learn in a fascinating afterword, is based on a real one in London that is open to the public.)

While Hugo Cabret is set in Paris, Wonderstruck in New York, and the saga of The Marvels centers on London, Selznick made most of the drawings for all of the works in his La Jolla studio, where he spends much of the academic year. Selznick moved to San Diego 11 years ago when his husband, David Serlin, took a faculty position at UCSD in the Communications Department. They still have a second place in Brooklyn, but Selznick feels that the move was serendipitous for his work.

“When we’re in New York,” he says, “the energy of the city seeps through the walls and the floors. There is a sense of millions of people vibrating. It sometimes makes it hard to work. San Diego has a profoundly different energy, that makes it easier to step away from distractions, to go to the space in one’s mind, to escape into the making of a story.”

Coincidentally, La Jolla has been the creative spot for one of the great innovators in 20th-century children’s literature, Theodor Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss.

And like Geisel, Selznick is an East Coast transplant. He grew up in East Brunswick, New Jersey, drawing and storytelling constantly in his youth. He later went on to study illustration at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) in Providence, but his passion at that time was for set design and acting. He took courses at Brown University, where RISD students had access to a variety of classes.

When Selznick applied to Yale University’s set design program and didn’t get accepted, he decided it was time to reassess. He moved to New York and took a job at Eeyore’s Books for Children in 1991, which became a launching pad for his literary career. The shop’s manager, Steve Geck, became a mentor and championed Selznick’s manuscript, The Houdini Box, which became his first book in 2001. (Geck has gone on to become a well-known editor of children’s books.)

There aren’t a lot of direct precedents for Selznick’s style of visual storytelling. Artist and illustrator Lynd Ward created wordless novels in the 1920s and 1930s, but they were targeted toward adults. The major surrealist artist Max Ernst arranged collages into quasi-narrative books such as The Hundred Headless Women, also in the 1930s.

Even though Selznick expanded the possibilities of storytelling with Hugo Cabret and Wonderstruck, he couldn’t help but push the limits further with The Marvels.

“I wanted to have a picture story and a word story each rely on itself,” he observes.

And lest you think 400 or so pages of drawings can’t involve you in a story as well as a written novel would, then The Marvels will likely persuade you otherwise.

Telling Stories Through Pictures

© Anette Carlsen, Zumapress