It’s only seven in the morning, and already sunlight is blazing through the east-facing windows. Downstairs at the Apostolic Assembly First Church of San Diego, members of the Community Assistance Support Team (CAST), a congregation made up of social workers, law enforcement, and the clergy sit at tables with brown oilcloth covers. Barry Pollard, founder of the Urban Collaborative Project, is on today’s speaker list. In the rising heat, he directs the meeting’s attention to Casa Sierra, a sprawling apartment complex behind Imperial Avenue in Southeast. “There is a lot of stuff going on in there,” he says.

“We did have a shooting yesterday at Casa Sierra,” one of five San Diego Police Department officers at the meeting says. “It happened about 10 a.m. It was a gang member, by the way, a member of ESD,” shorthand for East San Diego. The police then run down the details of four additional shootings in Southeast in the last week alone. One of them calls it March Madness. “There’s a lot of bad blood going on right now.”

March 11 was unofficially designated by the rival gang Bloods as “Crip Killing Day,” says Bishop Cornelius Bowser, a member of the Commission on Gang Prevention and Intervention. He explains the code: The third letter in the alphabet is C, and the 11th is the letter K. March 11. 3/11. C-K. Crip Killing Day.

“No one is coming to rescue us”

Sam Hodgson

A tall, graying ex-jock, Pollard has ideas about how to fix this community. He is not alone. The Jackie Robinson YMCA has a community response team that advocates for survivors of violence. SDPD has a Crisis Response Team, and they run curfew sweeps. The San Diego Compassion Project provides crisis intervention and long-term care to the families of murder victims, and CAST provides faith-based assistance toward helping calm tensions and reducing the potential for gang retaliation. Former City Councilman Tony Young is back in public life with RISE, a nonprofit geared toward urban leadership. “I believe they’re all having some impact on the issues in Southeast,” he says of the various organizations. “Many of them are doing difficult and hard work.”

Food and music and clean streets tend to be Pollard’s specialties for urban turnaround. He likes public art and block parties. Neighborhood bike rides. Neighborhood gardens. For example, his Urban Collaborative, an outreach of approximately 20 community members engaged in making “safety, civic pride, health, and beauty a neighborhood practice” in Southeast, has by now hosted two Taste of Southeast nights that put gourmet food trucks and live jazz and neighbors together at one of the bloodiest intersections in the history of Southeast: the Four Corners of Death, otherwise known as where Euclid meets Imperial.

If Pollard’s idea seems apple-pie ordinary, he asks the panel to consider that these are the kinds of events enjoyed across San Diego in neighborhoods everywhere. Everywhere, that is, but in Southeast. “What I’d like to do is get a cleanup going, with the idea that the Casa Sierra residents get involved. We can be the group that supports them.” He thinks a neighborhood cookout will do the job. “Hot dogs. Simple. A lot of people feel like they’re alone.” Pollard could be right. “The city has no plans,” he says. “It’s completely up to us. No one’s coming to rescue us.”

That sentiment is echoed by Michael Brunker, executive director of the Jackie Robinson YMCA. Brunker has long been an activist for peace in Southeast. “Any time people come together, good things happen. When people take real ownership, they become more aware of the situation. It’s not all about law enforcement. People have to realize that they have to save their own community.”

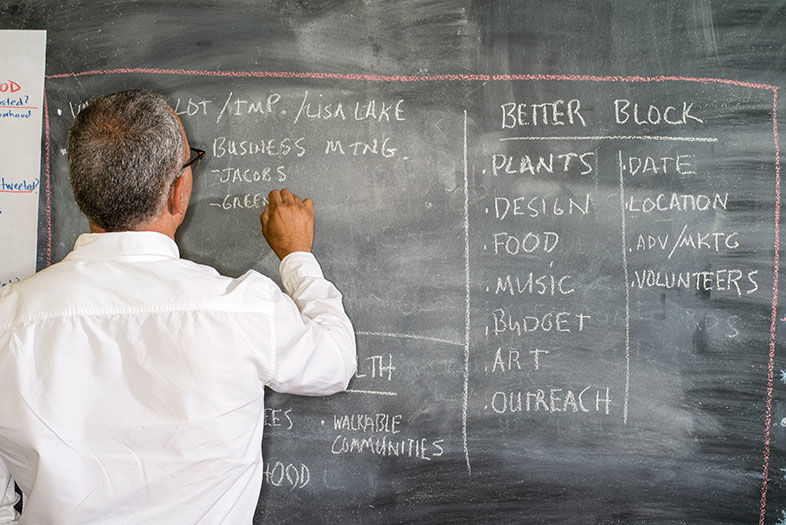

Barry Pollard gets up from working at a desk in a small two-room office suite on Logan Avenue that he calls the Urban Collaborative clubhouse but that, according to the sign out front, was once an insurance office. An entire wall inside is blackboard (“It’s paint. You can get it at Home Depot. Nine bucks,”) on which notes are chalked: Plants – Design – Food – Music – Budget – Art – Outreach. There’s a coffeepot, and odds and ends of repurposed furniture. In the back room is a silkscreen machine. It’s for the kids, he says, to learn how to screen designs and sell t-shirts.

Pollard is in the middle of emailing City Councilmember Myrtle Cole’s office. “I’m trying to get some bike lanes painted green. She says it’s a matter of public opinion. I say it’s a safety issue.”

Pollard is 61. Born and raised in Southeast, he played college football at the University of Louisiana in Lafayette. “I was their first black quarterback.” He says the NFL’s Cincinnati Bengals expressed interest, but that he went into the human resources field instead. He retired as director of human resources for Kaiser Permanente, and three years ago he mapped out his idea for the nonprofit Urban Collaborative on his dining room table.

“It was Plan B if I didn’t win the election.”

He says his own introduction to politics came when he tried to plant a community garden on a vacant lot. “I was told by the city that it would cost $30,000 just to put in a water meter. The shortest route,” (or so he thought) “would be to run for office.” Pollard campaigned against Tony Young in 2010 for city council, and again in 2013 when Young quit the Fourth District council seat. Pollard lost both times. “I’m still chipping away at my campaign debt.”

But his brush with politics was an eye-opener. “For one thing, these local elections have little to do with the community needs. They all have to do with business and labor. There’s no gray area.”

The lot in question, by the way, was still vacant the last time he checked.

“Disruptive innovation,” Pollard will say about it later. “That’s a term I’m trying to coin over here for people to embrace. It means disrupting the norm and getting people to think outside the box. It means challenging the city to eliminate some of the red tape around making change, and to give communities a little more flexibility in making things happen.”

“No one is coming to rescue us”

Barry Pollard’s plans for neighborhood engagement include trash pickup, block parties, community gardens, and cookouts.

Barry Pollard’s plans for neighborhood engagement include trash pickup, block parties, community gardens, and cookouts.

The Urban Collaborative was able to start a community garden on a different lot, however, and his team painted a bright mural on the fence behind it. “Drug dealers and crimes used to be committed there. Now, neighbors grow tomatoes and bell peppers, cilantro, things like that. A lady named Carmen—she sort of adopted it. It hasn’t been vandalized, except for a little graffiti that we cleaned up.”

Pollard likewise counts Food 4 Less among the biggest battleground victories to date for the Collaborative. “We got the residents involved in writing a certified letter to the CEO of Kroger, the grocery chain’s parent company, about the subpar food they had on the shelves.” Pollard included candid photos he had taken of in-store displays of gray-green meats and moldy fruit for sale. “Kroger pumped a million dollars into an upgrade of the facility. But I don’t want to think for a minute they were benevolent towards the little black and brown community here. It was because of the amount of money Food 4 Less was losing because residents were leaving the area to do their grocery shopping elsewhere.”

In what way has the grassroots organization failed Pollard’s vision? “Getting recognition from outside funders,” is his ready answer. “The apprehension they show around investing money in this community. And not just throwing money at problems. I mean, don’t write checks for $400,000 and then just walk away. That’s inviting failure. Instead, give us an action plan.”

Pollard raised $50,000 to launch the Collaborative. (He does not yet draw a salary.) “We’d like to get $100,000 this year.” The main obstacle to attracting such investment money, he explains, is the poor return on investment that Southeast has shown on past investments made to similar community benefit organizations. “The money goes into a black hole. Look around—people say it’s getting worse [rather] than better. Investors are interested, but they’re apprehensive.”

“I want to see this turned into an arts center for the neighborhood.” Pollard stands outside the old Valencia Park library on the corner of 50th and Imperial Avenue. The books are long gone and the building has stood empty and unused for decades, the lot choked with weeds and litter. “I went to this library when I was still in elementary school,” he says. Around the back is a dirt lot with a cement pad that, in the Urban Collaborative’s view, would make a nice playground for kids. “And a meeting space. You could have music here.”

In the field, Pollard remains in constant motion. “That’s going to be our art center for a day,” he points across Imperial to one of the storefronts in a mini-strip mall. He also has plans for the sizeable dirt lot next to the National Crossroads female ex-offender re-entry home: another community garden.

“He just walked in the door one day, and he said, ‘Hey, here’s what we’re doing. Would it be of benefit to your ladies?’” Lisa Grossman runs the center with her mother and her sister. Her answer was yes. “The Urban Collaborative will teach the women here about healthcare options. And the women will also help out in the Urban Collective neighborhood cleanup. A lot of our ladies have never done anything like that before.”

Pollard ignores a rusted “Private Property” sign, steps over a chain blocking a driveway, and looks around the back side of the businesses that face Imperial. A blonde woman coming out of a duplex approaches warily, wanting to know what he’s doing. She says her father owns the property.

“We’re planning a neighborhood cleanup,” Pollard says. Would she be interested? Yes, she would. He strolls down 50th at a rapid clip toward the Casa Sierra apartments. Roosters crow from someone’s backyard. “If it was up to me,” he says, “I’d mow all this down and start over. Why? Density. There are too many units crammed into a small space.” He points to porches stacked with discarded furniture, a pile of doors left out in the weather, a broken window papered over with cardboard.

“We’ll get some trash bins donated from EDCO, and we’ll have some food,” he says to another curious neighbor about his cleanup day. “Hot dogs. And weed whackers. How hard would it be to clean all this up? What are we waiting for? Someone to come in and rescue us?”

In a perfect Southeast without gangs and the violence that continues to plague that community, Barry Pollard might fancy himself as the welcoming committee. “I would like people to come over and visit and see the change taking place. Put aside all the misconceptions and fear. We don’t bite.”

“No one is coming to rescue us”

Urban Collaborative Project’s Barry Pollard, a native of Southeast San Diego, wants to help residents clean up the neighborhood themselves—even if it’s one block at a time.