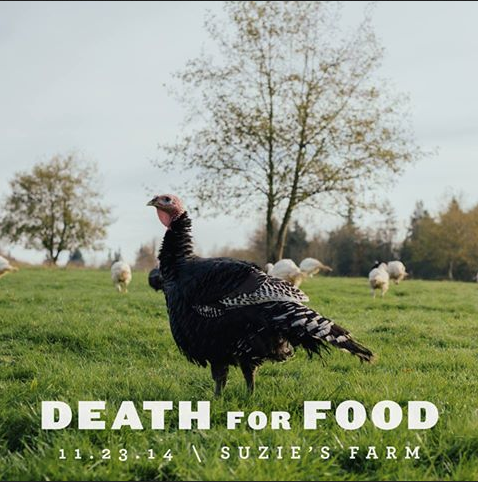

Some San Diego meat eaters were going to kill animals for food. A vegan activist lawyer staged an international campaign to stop them. That’s how Death for Food became one of the most controversial food events the city has seen in years. It made national news, and resulted in this cover story in San Diego CityBeat.

I’m highly biased in this debate. Months ago, I agreed to collaborate with Death for Food creator Jaime Fritsch because I believe in the educational philosophy driving his project. You can read why here, and read my initial reaction to Pease’s campaign here.

Basically, Death for Food invites omnivores to humanely kill their own dinner. Not for alpha-species thrill or Ted Nugent-esque blood sport. The idea is to reconnect meat-eaters to the life behind their meat, and let the emotions of that process guide their food decisions from that point on. It’s a movement against how meat is currently produced in America: anonymously and industrially.

Vegan activist Bryan Pease started an international Change.org campaign to stop the event, set to be held at one of the city’s most progressive and ethical food compounds, Suzie’s Farm. Without contacting the farm or organizers to see what the event was truly about, Pease made his best guess and portrayed the event very negatively, including the term “torture animals.” The hate mail and hate phone calls flooded into the farm and Death for Food creator, Jaime Fritsch. It caused financial harm to both. Since the protest, Fritsch has been accused of some pretty vile things. Animal abuse. Damaging children (a father brought his son to participate). Profiteering off animal slaughter. Insanity.

What’s been missing in the press coverage of the event is in-depth insight from Fritsch himself. The basic questions: Why invite people to a farm to kill their own dinner? Is that a progressive way to educate omnivores and promote responsible meat consumption? Or is it just sick in the head?

Here is Fritsch speaking about Death for Food, in his own words:

Why are you doing this?

I really don’t like answering this question. When you tell people what your purpose is, you pre-ordain their experience. It defeats the entire concept of Death for Food. Which is—by immersing yourself in the process, you fully experience it and integrate it, instead of having a preacher at a pulpit telling you how to feel. Now I feel I have no choice. My hope for the participants is that they integrate the process of meat back into their lives. That includes knowing about the life the animal lived, smelling the fresh air and the sunshine it gets, knowing it was a living, breathing, sentient being—and then understanding the magnitude of killing it. In my experience, afterward many people will slow down a lot, even just how they physically eat meat. They’ll chew it more, taste it more, think about where it comes from. By doing that, they’ll actually assimilate the food and nutrients more efficiently.

Sounds like some hippy dippy bullshit.

That’s science. When you think about food and concentrate on what you’re eating, you start to salivate and activate your digestive system. And what happens if you’re assimilating your food more efficiently? You need less. I’m not saying people should eat less meat. I do believe that—but I don’t preach that. After experiencing Death for Food, they tend to eat less meat. But not because I or anyone else told them to. Because they experienced killing first hand and felt the magnitude of it. Integration.

Can’t I just intellectualize it? Is it necessary to kill the animal myself?

I feel direct experience is the only way to experience that magnitude. It’s contagious, too—taking that brave step of looking at things and experiencing things in a real way. This is about self-trust. I’m going to jump in and I’m going to figure it out myself. We live in a world where things like the food pyramid tells us what to eat and what not to eat. Religion tells us that humans are innately greedy and bad and sinful and that we can’t be trusted. Science tells us that our bodies are not amazing and regenerative, but unreliable and in need of medicine and technology to regulate and improve them. A big part of what I’m saying is—you can be trusted. If you’re like me and feel a need to eat animals, you can trust yourself to eat them. You don’t need some professional to endorse your decision.

What made you start doing this?

For years I ate only humanely raised, very high quality meat—the best I could possibly find. But it would still come just wrapped up cold. And I started wondering if chicken was ever actually a chicken. If pork was actually ever a pig. I realized there’s a big disconnect between the life of the animal and the meat in the grocery store. One of the most shocking things about Death for Food is when you kill something and you remove the fur or the feathers. It starts to look like meat again. But there’s one key difference. It’s warm. The body temperature is warm. I needed that.

Why is that so important?

All meat we touch in a typical American kitchen is cold. When you touch it as you’re eviscerating just after killing it though, it’s warm. There’s still energy—actual caloric heat energy. It just had a heart that was pumping blood. It’s a shattering moment. It looks like meat, but it feels like life. It’s this in-between state. That’s when you associate meat with the live sentient being that it was.

Does the experience end there? Are there repercussions?

I think people come to Death for Food for an initial experience to get them started. We provide participants with resources for procuring locally raised, whole animals and help them meet local farmers and ranchers doing good things. We’re also starting a meat collective in San Diego where people can continue to take classes on slaughter, butchery, charcuterie, etc. It’s not a one-time “Get your Death for Food shot, and you’re good for life!” It’s a highly rewarding path to continue along after the event—to reconnect with the process of your food. On a very basic level, what participants have said about the way they think about and eat meat afterward: More thought, more responsibility, less meat.

Did you expect a protest like the one from Bryan Pease?

No. When I was in Portland, I had significant dialogue with hardcore animal rights activists—guys who have broken into places to set animals free, set fires to places doing animal research. And they were down with Death for Food. They said, ‘If you’re going to eat animals, please take a look. Please be honest with yourselves.’ I actually thought that was what we were going to get. I thought we’d get some heat from people who didn’t understand it, but I could talk to them and explain it.

Did it make you angry? Sad? Vengeful?

I see Death For Food as a question, not an answer. The Change.org campaign denied people the means to ask that question. I was shocked, because while I know it wasn’t a perfect scenario for animal rights activists—they’d prefer we just don’t kill animals for food at all—my experience has been that it’s a step in the right direction for them. Even though Bryan Pease fundamentally disagrees with what I’m doing on the basic level of killing animals for food, I think he knows I’m not the real enemy. Hopefully someday he will launch a campaign against factory farming and I’ll have his back in that fight. I respect his position that animals have unique personalities and feelings and we should not kill them. I’m not asking him to pat me on the back or anything. Our feelings on fighting animal cruelty overlap in many places but, like he has said, you have to draw a line somewhere. He does, and I respect that.

What sort of people are objecting to the event?

Objections are coming from hardline animal rights activists who believe humans shouldn’t kill animals for food, period. Honestly, I can respect where they’re coming from because I’ve entertained that sentiment myself and still wrestle with it sometimes. One guy told me he signed the petition because he felt like it should be held at a ranch, not a vegetable farm. And you know what? In retrospect, he was right. Suzie’s was not the right venue for Death For Food. From what I can gather, hardline animal rights activists also take the stance that “humane ranching” advocates like myself are even worse than industrialized ranchers because we raise these animals with the same care as pets and then betray their trust when we eat them.

Is this worse?

You really have to ask me that?

Yes.

I don’t think anything could be worse than a factory farm system. It’s hell on earth. The fact remains, though, that I want meat and I want it on what seems like an almost cellular level. I understand the desire to not hurt animals. That’s how this entire project began. For me, the abstinence solution just didn’t work. Treating animals well during their lives—and giving them a quick, as-painless-as-possible death—does work.

What about the more extreme objections to Death For Food? That meat eating is a fundamentally bad thing—both environmentally and health-wise?

Those arguments are based off the factory meat system, with good reason. Death For Food that promotes local, holistic farms that mimic nature and utilize plants and animals to restore functioning, food producing ecosystems. That’s dangerous for vegan activists because it undermines the core arguments of vegan activism. We advocate a deeper connection with food in order to find a resonant system of eating for yourself. Daeth for Food usually results in people eating far less meat, and far healthier meat. We require humane treatment of animals in life and in death both within the project and beyond, when we use our dollar power to purchase ethically produced food. By eating a more reasonable amount of meat and taking part in the process ourselves by sourcing whole animals from local farms, we make healthy meat affordable to all.

And you think activists are threatened by this?

I hope not, because logistically I think a network of local, omnivorous food systems is the only thing that’s going to feed Earth’s population without completely destroying its ecology. I don’t want to hinder any implementation of that by further inflaming the current vegan vs. omnivore fight. This planet evolved over four billion years around local, omnivorous food systems. That’s just what works for us, environmentally speaking. But removing factory farms from the discussion seems to dismantle every pragmatic argument for a wholesale, global conversion to veganism. I can see how that alone could be a catalyst for a whole new round of arguments. The bummer of it all for me is that I’m 95-percent vegetarian. Ironically, it’s this tiny bit of meat I’m fighting about eating.

It didn’t seem like there was a “tiny bit of meat” set to be served at Death for Food. It seemed like a feast.

Right. It was a family-style meal with many different types of local and seasonal produce, fish and meat. But the idea was you could eat as little or as much as you wanted as an exercise in learning to be your own barometer with what you need in your diet. I tried not to talk about that too much because, again, I didn’t want people to come in feeling like they had to take a half a bite of everything and pretend like they were being “good, responsible omnivores.”

Some vegans have argued that no sane person would willingly kill an animal.

With Death for Food, sane citizens experienced responsible animal slaughter and reported that it was challenging but worthwhile. Most of them also decided to continue eating meat, but do so with more responsible parameters. Is that the action of an insane person? Or are certain parts of life merely challenging, and Death for Food attendees are people willing to face that challenge head on.

You say animals are humanely killed at Death for Food. How so?

We use a process where we blood-let very close to the jawline and position the animal so that the first blood that comes is from their brain. We use a razor sharp knife. They lose consciousness in two to six seconds. I’d compare it to when you’re cut with a scalpel and you don’t even know until you see the blood. When done by a professional, the animal doesn’t even realize what happened.

How do you know that’s the best way, for, say, the lamb that you were going to kill at Suzie’s?

That’s advice from holistic ranchers. The other way is to shoot the lamb in the head. But they have such small brains you can easily miss, causing needless pain to the animal. You also destroy the head, which is a lot of food. Stun guns are also controversial. It mostly works, but it can also just hurt the animal and not render them unconscious. I’ve seen the killing process at holistic, small farms and ranches from Washington to Mexico—and the most ideal method I’ve seen is a professional wielding a sharp knife and going for the bloodline close to the brain.

But you’re having regular people kill their own dinner. Not professionals.

We have a very good support staff with a lot of experience. I’m there with you. That’s to keep you and the bird from injuring yourselves. That said, there is potential for it going wrong. I can’t insulate people from that. Life is messy. Even the best, most humane ranchers I’ve ever met will admit it’s not always a perfect process and that occasionally a humane kill goes badly. In America we’ve taken this sort of hyper-sterile, ultra-safety path to everything. I actually see that as part of a larger problem—the refusal to engage with anything dangerous. The process at Death for Food is not only dangerous for the animal—it’s dangerous for the participants. One of those turkeys could easily break your nose with its wing. It could take an eye out with a claw. Death for Food is a larger idea of going headfirst into life and embracing the challenging parts along with the good parts. Typically when we say ‘embrace life,’ we mean hug your neighbor. Well, part of embracing life is embracing the challenging parts, too. Like holding your loved ones’ hands as they die. Not as they ‘pass on.’ As they die. Or spending time with the terminally ill. Whatever you want to do. Embracing life fully means embracing death. Conversely, denying death means denying life.

People have complained about the cost. They’ve said it’s astronomical and accuse you of profiteering.

The max possible sales for the event was $12,900. There were only going to be 75 attendees. And there were only a handful of higher-cost tickets–$200-$300, where people were able to take the morning class to kill their own chickens and turkeys, and take them home for Thanksgiving. Let’s break it down with our projected costs: venue fee ($1,000); food service staff ($2,000); tables/chairs/linens/wares ($2,200); food ($2,500); beverages ($2,500); harvest chickens ($500); harvest turkeys ($1,000); decor ($200); cooking equipment ($750); kitchen staff ($480); lighting ($250); A/V and sound ($200); harvest station construction ($2,000); photo exhibition ($1,000); wood for fires ($150); contributor flight/hotel ($500); menu printing ($200). That’s $17,230 and we hadn’t even yet budgeted security because I wasn’t thinking we’d need it until things got crazy. It’s also worth noting none of the chefs, speakers, or my event coordinator were receiving a cent. They were all doing this for free.

So you would’ve lost over $4,000.

I don’t think so. People support this project. Donations come in, vendors politely refuse payment or give me a big discount to show support. I bet in the end I would have at least come close to breaking even. I guess I just trust life like that.

If this is about education and not profit, couldn’t you silence critics by becoming a nonprofit?

It doesn’t matter to me if Death for Food is labeled a nonprofit. It’s a negative profit. It hemorrhages money.

There were accusations that you weren’t using USDA-approved meat, and that’s partly why the event was canceled because that would be illegal.

My top priority is using the most humane, best meat possible. I wouldn’t put on an illegal event. If there were questions of the legality, I would have properly addressed them.

Have you heard from people who attended the first event and how it affected them?

Dozens. People tell me it changed their lives.

The Controversy: Death for Food

by Jaime Fritsch