In competitions like the World Cheese Awards, cheese is judged for qualities like aroma, flavor, texture, and appearance. Is the rind cracked? Does the cheese smell fruity, or does it have unpleasant hints of barnyard? And while most people look to the popular mantra “farm to table” to rate their fromage, they’re missing one valuable piece of the equation: science.

It turns out that it’s not so much the milk that makes cheese smell and taste the way it does—it’s the microscopic communities of bacteria and fungi that flourish in the milk and on the cheese’s growing rind that are responsible for creating the floral, buttery taste we like so much.

This UCSD Professor Is Using Science to Make Cheese Taste Better

Rachel Dutton

And at the forefront of achieving that ultimate mouthfeel is Rachel Dutton, an assistant professor in UC San Diego’s Division of Biological Sciences.

Dutton’s research on microorganisms enables her to tell a cheesemaker what’s needed to achieve a certain aroma, a desirable mouthfeel, or a specific flavor profile. Her research has the potential to directly impact the quality of the artisanal cheeses we crave.

The idea sprouted several years ago when Dutton was studying the salt marshes of Cape Cod. One day, a generous colleague shared a tasty piece of Tomme de Savoie. While she nibbled, its textured rind caught her eye. The layered structure reminded her of what she’d been studying in the salt marshes, so she kept a piece to see if she could isolate some of its microbes in her lab.

Cheese, it turns out, has a simple ecosystem. Instead of thousands of microscopic species thriving and adapting the way they do in a salt marsh or a scoop of garden soil, a bloomy, smelly cheese rind might contain only a dozen. Diverse, but not overly so.

This UCSD Professor Is Using Science to Make Cheese Taste Better

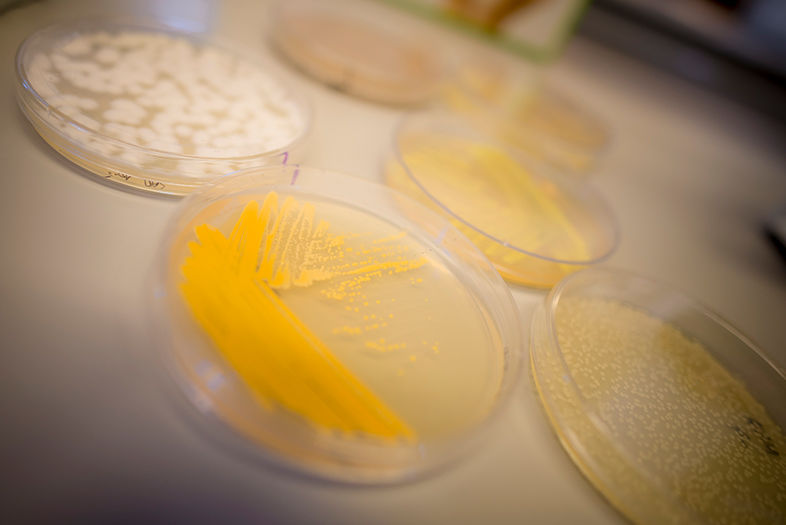

Microbial cultures in Dutton’s lab | Photo: Erik Jepsen/UC San Diego

“With cheese, we can grow every single organism on its own in the lab and start to understand how microbial communities actually form,” Dutton says. “We can combine different types of species and see how they behave when they’re together versus apart, and we can follow community development over time.”

It also means that microbial DNA from cheese can be sequenced. Backed with five years of funding and her own lab at Harvard, Dutton and colleague Dr. Benjamin Wolfe set out to map the diversity of organisms across more than 130 cheeses from 10 different countries, publishing their findings in the journal Cell in 2014.

“We were able to get a basic understanding of how these communities form and change by going to cheese caves, taking samples over time, and sequencing them,” Dutton explains. “That laid the foundation of the work that is now going on in my lab here at UC San Diego.”

Dutton’s work has gained widespread recognition, turning her into a sensation among the nation’s artisanal cheese community, and a sought-after darling of the food community. It wasn’t long before she showed up on the radar of notable food science writer Harold McGee, fermentation guru Sandor Katz, and famed chef David Chang, who was experimenting with fermentation projects at his Momofuku restaurant in New York City.

At the time, Dan Felder—now cofounder and chief information officer of Pilot R+D, a culinary science company based in Northern California—was working in Chang’s research and development kitchen. Felder says they were seeking a process that would mimick the making of katsuobushi (Japanese fermented bonito) with pork tenderloin.

“There’s a lot of overfishing of bonito and it’s quite expensive,” Felder says. “We felt like we could mimic the core parts of the process. As we got deeper into the project, we were getting into an area that we didn’t know enough about.” That project led them to Dutton, who bridged the gap between the culinary and scientific worlds.

This UCSD Professor Is Using Science to Make Cheese Taste Better

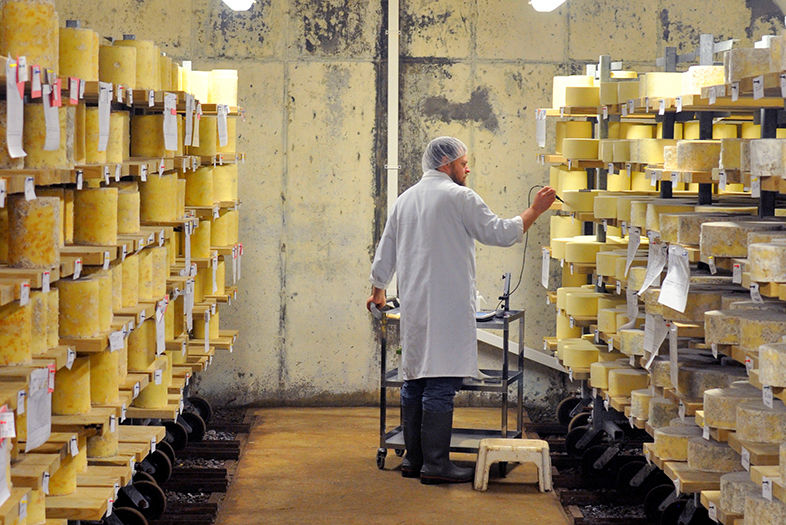

Jasper Hill Farm in Vermont, where Dutton researched the cheesemaking process

“Rachel loves food and is intensely curious. It’s not solely an academic passion for her,” he adds.

Big-name chefs aside, Dutton’s rapport with the food community is strongest among cheesemakers. Before starting her Harvard lab, Dutton spent three months working in the creamery of Vermont’s Jasper Hill Farm forging a deep friendship with cheesemaker Mateo Kehler, while also gaining experience and a solid understanding of the cheesemaking process. Luckily for Dutton, that hard work also included access to Jasper Hill’s seven vaulted cellars where a broad range of cheeses are ripened—a veritable zoo for an eager microbiologist.

“Rachel came to us with this incredible opportunity to look deeply at our cheese in a way that I don’t think many other cheesemakers have,” Kehler says. “Our Bayley Hazen Blue is the most deeply studied product out there, considering the amount of sampling and full genome sequences at multiple stages and multiple batches.”

Kehler ended up with an incredible view of a world that cheesemakers have intuited for centuries, but had never gotten to see firsthand. It was an opportunity to understand why some batches of cheese express an amazing complexity and diversity of flavor, while others fall a little flat.

The answer—which has to do with individual microbes that behave differently when they’re in a community—would have remained elusive if it weren’t for the connection between the microbiologist and cheesemaker.

It didn’t take long before Kehler was a believer in Dutton’s work and decided to build a lab of his own, complete with two full-time staff microbiologists. Today he can extract DNA and get a partial sequence of his cheeses for around $5 a sample, and he’s now adapting his business to respond to what he’s finding in the lab.

This UCSD Professor Is Using Science to Make Cheese Taste Better

Monitoring the cheese cellar at Jasper Hill Farm

“We changed the way we feed the cows—eliminating fermented feed—and it changed the microbiology of the milk, because it altered the microbiology of the animal environment. We were able to measure that,” he says.

Thanks to the world Dutton’s science opened up, Kehler is isolating native cultures and using microbes indigenous to his own farm to increase the potential flavor diversity of the cheeses being made there, instead of buying a limited set of starter cultures from companies like DuPont or Cargill.

“Microbiologists are the new rock stars of the food world,” Kehler says. “I don’t think Rachel understood that people were going to be so interested in what she was working on.”

With only a year under her belt at UC San Diego, her lab is already running full tilt. Six freezers are loaded with cheese samples; cabinets are full of beakers, petri dishes, and science equipment; and a handful of white-coated PhD students are hard at work.

Now she’s got her eye on local beer makers and has already gained a following among the city’s fermenters. At February’s Fermentation Festival, Dutton spoke with microbiome expert Rob Knight of the American Gut Project, packing the tent with close to 300 people.

She had them from the get-go: “Who likes cheese?”

Say Cheese!

Venissimo will host a Science of Cheese tasting at Liberty Station’s Moniker General on July 19.

$55

What’s in Our Favorite Cheeses?

The words may get a bad rap, but plenty of bacteria and fungi are helpful to us. Certain strains and microbes give the cheeses we love their distinct flavors.

“The more I learn, the more I’m inspired to explore. Every week I see a handful of cheeses that I’ve never seen or tasted,” says Robert Graff, a specialist at Venissimo Cheese. “The diversity of flavors and textures is staggering, and the potential for cheesemakers to create new offerings is limitless. This is due to the biodiversity of individual cheeses, as well as the environments from which they come.”

To satisfy our own curiosity—and to wow people at our next wine and cheese party—we asked Graff to give us the lowdown on what’s inside our favorite fromages.

P. roqueforti fungus gives Roquefort and Gorgonzola their pungent aromas.

P. camemberti gives Camembert the white mold on its rind.

Propionibacterium is the bacteria responsible for the air pockets (eyes) in Swiss/Alpine cheese. These cheeses are nutty.

Brevibacterium linens are the bacteria in washed rind (stinky) cheeses such as Limburger and Muenster. It’s responsible for turning the rind a reddish orangey color and makes them smell like gym socks, but taste wonderful. These cheeses are meaty, brothy, and pungent.

Geotrichum candidum is a white mold used in a number of cheeses but is probably most famous for being responsible for the ‘brainy’ rind on young goat cheeses. These cheeses are tangy, sour, and bright.

This UCSD Professor Is Using Science to Make Cheese Taste Better

UC San Diego assistant professor Rachel Dutton in her lab. | Photo: Erik Jepsen/UC San Diego