Remember the kids’ song “There Ain’t No Bugs on Me”? Totally untrue. There are lots of “bugs” on us—bacteria, viruses, fungi—trillions of them. They’re on our skin, throughout our guts, possibly in our brains, pretty much everywhere. Don’t recoil; it’s a good thing. Together, this community of microbes makes up your microbiome.

“The vast majority of microbes on our bodies are doing something at least harmless and frequently beneficial for us,” says UC San Diego computer scientist and microbiome researcher Rob Knight. “That’s just as well, because they outnumber us and—especially with their diversity and genetic repertoire—outnumber us to such a large extent that, if they were mostly out to get us, we’d really be in trouble.”

There was a time when we thought the only good microbe was a dead one, and developed a vast arsenal to make that happen—antibiotics, antibacterial soaps, Lysol till the counters glistened. But our microbial knowledge has become a lot more nuanced, thanks to Knight and other microbiome researchers around the world.

Call it the rehabilitation of germs. Yes, there are still pathogens to watch out for—Salmonella, Streptococcus, certain strains of E. coli—but recent work has illuminated an astounding variety of friendly microbes that contribute to metabolism, mood, and basic good health.

Bugs as Drugs

Knight is a scientific workhorse. He’s only in his early 40s, but his lab has already published more than 400 papers. He is part of a movement of researchers seeking to better understand how these microscopic stowaways affect our biology.

Generally, healthy microbiomes contain a diverse range of organisms looking after their own interests and, by extension, ours. But sometimes that balance gets out of whack, allowing disease-causing bugs to flourish.

Knight points to C. difficile, a bacterium that infects the colon and often resists antibiotics. The solution? Fecal transplants. The patient swallows a pill containing a minute amount of hospital-grade stool from a healthy person (yes, poop is regulated by the FDA as a drug), and the microbes it contains outcompete the C diff.

“It’s like the C diff. are a monoculture of weeds, and when you introduce the diversity of microbes that are good, they just outgrow the weeds,” Knight says.

This early success may be just a drop in the bucket. An individual’s microbiome could dictate which foods they should eat or how they respond to certain drugs. In the future, to reduce side effects, oncologists may select chemotherapies based on a patient’s microbial community.

Scientists are also studying how microbes help manage the immune system. Australian researcher Mimi Tang is using Lactobacillus in oral immunotherapy against peanut allergies, and has gotten complete remissions in some patients. Microbes and the compounds they produce, called metabolites, could also lead to new drugs.

“Microbes in your gut are producing antibiotics,” Knight says, “and that’s a source that basically has not been mined at all.”

Feeding Your Microbiome

Given the expanding evidence that a diverse microbiome is essential for good health, there’s been increasing interest in augmenting these communities by adding microbes (probiotics) or feeding existing microbes (prebiotics). Many people have incorporated microbe-rich fermented foods into their diets—think yogurt, kimchi, kefir—but their mechanisms aren’t fully understood.

“There’s a fair amount of evidence that fermented foods as a whole have a beneficial effect,” Knight says. “It’s a much more open question whether there’s a benefit from isolated components of the whole food. For example, if you take the bacteria in yogurt but don’t have the matrix of the fermented milk, will it still have a beneficial effect? The evidence is a lot less clear.”

Knight likens probiotics to taking medicine. If you have a specific condition, certain clinical probiotics might help. However, if you’re already in good shape, there’s little evidence that probiotics will make you healthier.

The Harm We Do

Prebiotics are a different story. To some degree, our microbial communities are what we eat. Bacteria like eating fiber, which can be scarce in Western diets. Unfortunately, a high-fat, high-sugar, low-fiber diet can favor the wrong microbes. “The high sugar feeds Gammaproteobacteria, like E. coli and its friends, some strains of which are harmful,” Knight says.

Antibiotics can also be a problem. They’re lifesaving, but they can also wreak havoc on the microbiome. Some researchers are experimenting with probiotics that would restore the appropriate bugs in these cases, but there’s a lot more to be said for prevention.

Describing his own family’s philosophy, Knight says, “We try to avoid antibiotics, but take them when they’re medically necessary. It’s about asking a doctor if there’s an alternative to taking antibiotics now. What would happen if we waited? And, if we waited, would we still be able to make that decision after a few days?”

Your Body Is Bugged

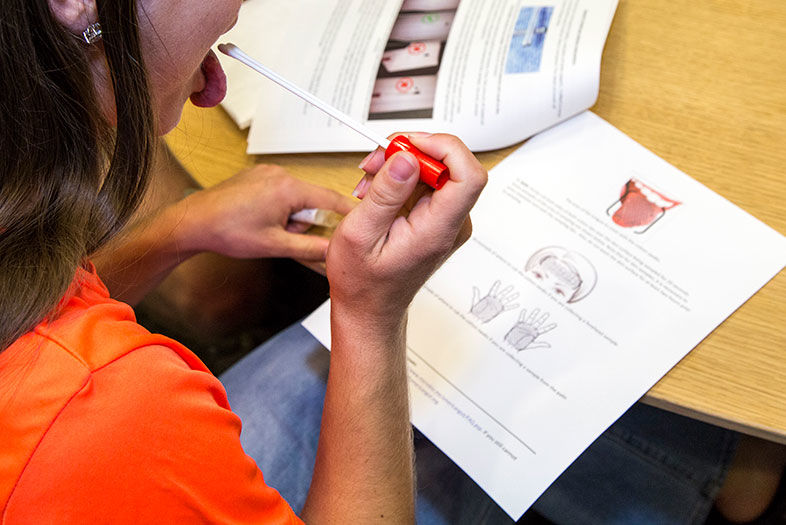

A student uses a sampling kit from the American Gut Project

American Gut

Knight is a big evangelist for the microbiome, spreading the word on what the current evidence shows and how that can affect people’s lives. He cowrote a recent book with Jack Gilbert called Dirt Is Good, which questions the wisdom of raising children in overly sterile environments. In other words? Let them play in the mud.

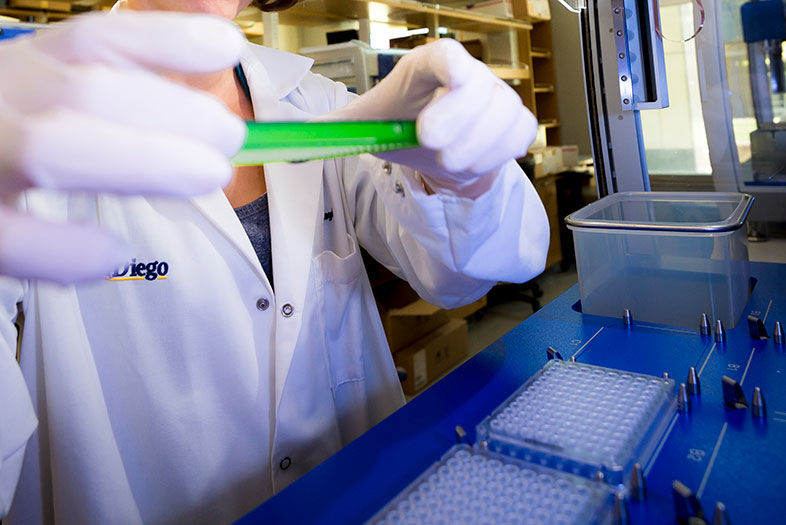

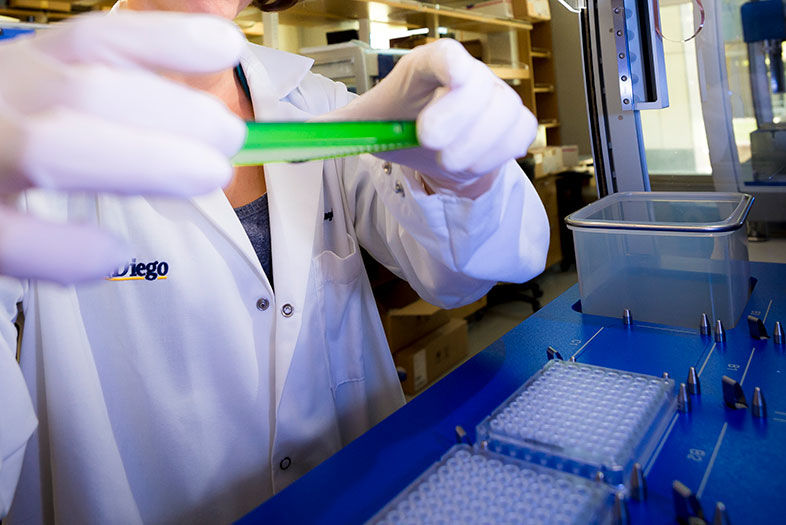

He also helped found the American Gut Project, which invites volunteers to send in stool samples to give scientists more information on microbiome diversity. So far, around 50,000 people have sent in their samples, essentially crowdsourcing microbiome science.

A recent paper from the project analyzed samples from 10,000 people and showed, among other things, that eating a wide variety of plants increases microbiome diversity and can reduce genes associated with antibiotic resistance.

What happens next? Knight can envision a smart toilet that would analyze your microbial DNA and metabolites with every flush and deliver a gut health report directly to your smartphone. Researchers are also experimenting with a mirror that collects and analyzes your morning breath.

“As you breathe on the mirror, it can whisk that breath away through pores in the glass, subject it to some sort of chemical analysis, and give you an instant chemical readout,” Knight says.

To lend a face to the numbers—literally—the mirror could come equipped with augmented reality technology that could show you what you might look like in 20 years, based on where your microbiome is going today.

“All the pieces exist, it’s just a matter of integrating it.”

Your Body Is Bugged

PARTNER CONTENT

Photo by Erik Jepsen